Student Notetaking for Recall and Understanding: A Lit Review Review

by Derek Bruff, CFT Director. Cross-posted from Derek’s blog, Agile Learning.

by Derek Bruff, CFT Director. Cross-posted from Derek’s blog, Agile Learning.

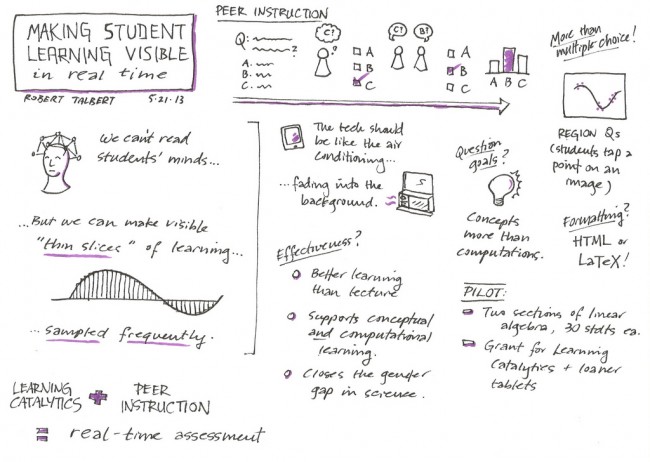

I’m giving a talk on sketchnotes in the classroom next week at Indiana University. (I’m following John (Engaging Ideas) Bean in their speakers series, which is just a little bit intimidating.) I’ve been using sketchnotes for my own notetaking practice since 2011, and I’ve found it useful for all the reasons I detailed in this blog post last summer. Next week will be the first time I’ve talked with faculty about using sketchnotes, either for their own notetaking practice or as notetaking method for their students, so I’m spending some time this week looking into the literature on notetaking. I haven’t found any studies of sketchnotes in the classroom, but I have found some interesting studies on other forms of notetaking.

In one forthcoming study by Pam Mueller and Daniel Oppenheimer, described in a blog post titled “Ink on Paper: Some Notes on Note-taking” by Wray Herbert, students were directed to take notes on what seemed to be a history lecture either longhand (pen and paper) or by typing on a laptop. Some students from each condition were tested on both factual recall and conceptual understanding half an hour after the lecture, and others were given a similar assessment one week after the lecture, after being encouraged to review their notes in the intervening week.

The results? Immediately after the lecture, both longhand and laptop notetakers did well on the factual recall questions, but the longhand notetakers did better on conceptual understanding questions. A week later, the longhand advantage was even stronger, with those students doing better on both factual recall and conceptual understanding questions. This, in spite of the fact that the students using laptops took more notes than the longhand notetakers! Here’s Wray Herbert’s summary:

“Those who took notes in longhand, and were able to study, did significantly better than any of the other students in the experiment — better even than the fleet typists who had basically transcribed the lectures. That is, they took fewer notes overall with less verbatim recording, but they nevertheless did better on both factual learning and higher-order conceptual learning.”

Herbert doesn’t mention anything about the laptops’ potential for distraction (Facebook, ESPN, shoe-shopping, and so on) and the paper by Mueller and Oppenheimer isn’t yet available in the journal Psychological Science, so I can’t say if perhaps the laptop notetakers fared worse because of off-topic use of their laptops. The fact that the laptop users took more notes than the pen-and-paper notetakers indicates that they paid a certain level of attention to the lecture, but I’ve observed, from the back of classrooms, many students take copious notes while also instant messaging and checking Tumblr. (Hat-tip to @SnarkySeverus for pointing out the distraction issue after I tweeted about this study last night.)

The most interesting part of the study in my opinion is the distinction it draws between factual recall and conceptual understanding assessments. The finding that taking more detailed and complete notes (via laptops in this case) helps with short-term factual recall but doesn’t help as much for long-term factual recall or higher level learning objectives is somewhat consistent with what I’ve seen in other articles on student notetaking.

Robert Williams and Alan Eggert’s 2002 literature review discusses the concept of notetaking efficiency, “defined in terms of the ratio between the number of conceptual points recorded and the number of words in the notes” (p. 175). They note that “the literature is mixed on the efficacy of efficient notetaking” (p. 176) at least when the outcome measure is factual recall. Some studies, like the longhand vs. laptop one described above, indicate that more verbose notetaking helps with short-term factual recall. Other studies show just the opposite, giving the edge to efficient notetaking for short-term recall. For long-term recall and higher-level thinking? There’s apparently not much research on this (at least as of 2002), but efficient note-taking shined in one study:

“Kiewra and Fletcher (1984) reported that notetakers emphasizing main points, rather than details, did better on both immediate and delayed test items over specifics, main ideas, and integration of ideas” (p. 177).

Kenneth Kiewra seems to be a student notetaking research rockstar. Active in the 80s and 90s, he is cited 23 times in this Williams and Eggert lit review. His other studies explored further this “main points” versus “details” element. In Kiewra (1987), 91% of students recorded in their notes the main points of a lecture, but not as many students recorded subordinate points (60% for secondary points, 35% for tertiary points) and very few students (11%) recorded the most-specific details of a lecture. The accuracy of “level 1” and “level 4” points recorded in students’ notes wasn’t predictive of their short-term or long-term test performance, in part because so many and so few students, respectively, recorded those points, but “level 2” and “level 3” accuracy were predictive of student performance. Here’s Williams and Eggert again:

“In fact, correlations between noted subordinate ideas and test scores were higher when a more general course exam was given four weeks after the lecture than when a lecture-specific exam was given only one week after the lecture” (p. 179).

These findings point to a Goldilocks zone: Notes that record only the biggest ideas from a lecture aren’t that useful, since recording subordinate ideas is predictive of test performance, but taking copious notes on everything–all the details–isn’t that useful, either, since more efficient notes are correlated with long-term recall and understanding. Here’s how Williams and Eggert sum this up: “The most effective notes highlight an overall framework for a lecture and embellish that framework with critical specifics” (p. 177).

These findings provide reason to believe that sketchnotes can play a useful role in the classroom. Sketchnotes are highly efficient by Williams and Eggert’s definition of efficiency: using doodles and diagrams to capture ideas means using very few words per idea. Sketchnotes are also useful, given their nonlinear nature, for capturing the structure of a lecture and the relationships among ideas in a talk.

Sketchnotes that only capture the biggest ideas in a lecture would likely not be that useful to students, in part because they don’t provide students with much to review after class. Reviewing notes seems to be very important for factual recall. In fact, when factual recall is the outcome measure, students are better off reviewing instructor-provided lecture notes than their own notes, according to another study by Kiewra (1985b)! However, another Kiewra study (1985a) showed that “reviewing notes made no difference on higher-order tasks involving inference, application, analysis, and synthesis” (Williams & Eggert, 2002, p. 183).

Sketchnotes that only capture the biggest ideas in a lecture would likely not be that useful to students, in part because they don’t provide students with much to review after class. Reviewing notes seems to be very important for factual recall. In fact, when factual recall is the outcome measure, students are better off reviewing instructor-provided lecture notes than their own notes, according to another study by Kiewra (1985b)! However, another Kiewra study (1985a) showed that “reviewing notes made no difference on higher-order tasks involving inference, application, analysis, and synthesis” (Williams & Eggert, 2002, p. 183).

As I noted above, one interesting aspect of the longhand vs. laptop study was the distinction it drew between factual recall and higher-level learning outcomes. It’s clear from Williams and Eggert that most of the research on student notetaking has used recall of factual material from lectures as the primary or only outcome measure. I’m not finding as much research looking at higher-level learning outcomes or learning as assessed through means other than exams.

This points to a key question when considering student notetaking practices: What’s the objective? If you’re interested in having students remember ideas from your lecture, then instructing them to take fairly detailed notes or providing them with your own notes to review is a good strategy. If you’re interested in more than factual recall–in conceptual understanding, application and analysis, evaluation and creative work (see what I did there?)–then it’s less clear from the literature what strategies to use, although there’s some indication that more “efficient” notes that capture main and subordinate ideas are best and that the “encoding” that occurs during notetaking is more important than post-class review.

And if you’re interested in helping students take notes on a class discussion instead of a lecture? I haven’t turned up any studies so far examining that context.

References

- Kiewra, K. (1985a). Examination of the encoding and external-storage functions of notetaking for factual and higher-order performance. College Student Journal, 19, 394-397.

- Kiewra, K. (1985b). Learning from a lecture: An investigation of notetaking, review, and attendance at a lecture. Human Learning, 4, 73-77.

- Kiewra, K. (1987). Notetaking and review: The research and its implications. Instructional Science, 16, 233-249.

- Kiewra, K., & Fletcher, H. (1984). The relationship between levels of notetaking and achievement. Human learning, 3, 273-280.

- Williams, R., & Eggert, A. (2002). Notetaking in college classes: Student patterns and instructional strategies. Journal of General Education, 51(3), 173-199.

Image: “spiral notebook,” theilr, Flickr (CC)

Leave a Response