Pedagogy for Professional Schools and Students

| by Richard Coble | Print Version |

| Cite this guide: Coble, R (2015). Pedagogy for Professional Schools and Students. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved [todaysdate] from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/pedagogy-for-professional-schools-and-students/. |

What are Professional Schools? | Signature Pedagogies | From Novice to Expert | Conclusion

Is There Something Wrong with Professional Education?

Recent commentators on American education such as David Brooks, William Deresiewicz, and Edward Farley have critiqued the general shift to career preparation in higher education. The charge against professional education tends to discern a disparity between career preparation on the one hand and general liberal education, the promotion of critical thought, and the advancement of thoughtful citizenship on the other.

A Crucible Moment: College Learning and Democracy’s Future, a recent publication by The National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement, an initiative funded by the US Department of Education, articulates this critique convincingly:

A troubling chorus of public pronouncements from outside higher education has reduced expectations for a college education to job preparation alone. Dominating the policy discussions are demands that college curricula and research cater to “labor market needs” and to “industry availability.” Still others call for an increase in “degree outputs”—much as they might ask a factory to produce more cars or coats…The call for educational reform cast only as a matter of workforce preparation mistakenly adopts a nineteenth-century industrial model for complex twenty-first-century needs. Reframing the public purpose of higher education in such instrumental ways will have grave consequences for America’s intellectual, social, and economic capital. Such recommendations suggest colleges are no longer expected to educate leaders or citizens, only workers who will not be called to invest in lifelong learning, but only in industry-specific job training (p. 9-10).

The critique thus warns that if education focuses squarely on market needs in professional preparation, it will fail to prepare students holistically for thoughtful citizenship and life itself. The stakes of such divisions have risen in recent years in the wake of proposed budget cuts and priority shifts, for example, in the Wisconsin and North Carolina University systems. Given this warning, what then is responsible professional pedagogy? Is there necessarily a strict boundary between professional and liberal education?

What are Professional Schools?

Professional schools provide terminal degrees that train students for a specific profession, such as careers in medicine, law, or religious leadership. In higher education, there is a wide variety of professional schools, each with its own basic requirements and prerequisites.

At Vanderbilt University, the professional schools include:

- Vanderbilt Divinity School

- Vanderbilt School of Engineering

- Vanderbilt Law School

- Vanderbilt School of Medicine

- Vanderbilt School of Nursing

- Owen Graduate School of Management

- Peabody College of Education and Human Development

In 2015, these schools had a combined enrollment of 6,123 students and employed 3,112 faculty members (See Vanderbilt University, “Quick Facts”). Moreover, 65.5% of all Vanderbilt undergraduates who go on to graduate study do so at a professional school, according to the Center for Student Professional Development.

Though professional schools provide graduate level degrees like the Master of Divinity (MDiv) for clergy or the Doctor of Jurisprudence (JD) for law students, their instruction differs from traditional research degrees like the Doctor of Philosophy in terms of focus and aim. Georgetown College’s student resources page makes a useful distinction:

The distinction between graduate school and professional school is somewhat like the distinction between basic science and applied science; the differences lie in the focus. In graduate school, students focus primarily on mastering a particular field of study. Graduate degrees do not focus on training a student for a specific career, although the expertise that is gained should ultimately be applicable to a field of work. In professional school, the student focuses more directly on preparing for a specific career. Coursework and training are rooted in traditional disciplines, but emphasize “real world” applications.

Does this distinction then prove the above critique to be true for all professional education?

Signature Pedagogies in Professional Education

Signature Pedagogies are characteristic ways of teaching in a discipline that promote “disciplinary ways of thinking or habits of mind” in students (Chick, Haynie, Gurung, eds., Exploring Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind, p. 1). In other words, signature pedagogies not only teach the content of a discipline, but also seek to train students to think as professionals or experts of the discipline itself.

Looking at signature pedagogies within professional education, it becomes clear that thoughtful professional teaching promotes both professional skills as well as critical thinking. As Lee Schulman’s article “Signature Pedagogies in the Professions” explains, professional schools seek to “form habits of the mind, habits of the heart, and habits of the hand” (p. 59). This means that professional schools teach knowledge, skill, and ethics applicable to the profession:

Professional Education is not education for understanding alone; it is preparation for accomplished and responsible practice in the service of others. It is preparation for ‘good work.’ Professionals must learn abundant amounts of theory and vast bodies of knowledge. They must come to understand in order to act, and they must act in order to serve (p. 53).

In other words, signature pedagogies in professional schools do not train students solely towards marketable skills (though this is certainly a facet of professional education), but seek to form the character of practitioners through a three-pronged approach of knowledge, skill, and ethics.

Examples of holistic approaches to professional education can be found in the “Professions” section to Exploring More Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind, eds. Chick, Haynie, Gurung:

Chapter 13

“Competence and Care: Signature Pedagogies in Nursing Education”

by Thomas Lawrence Long, Karen R. Breitkreuz, Desiree A. Diaz, John J.

McNulty, Arthur J. Engler, Carol Polifroni, and Jennifer Casavant Telford

Nursing education instills “a professional ethos characterized by empathy, ethical behavior, and social justice” through a combination of liberal arts education, skills training through simulation and field placement, and standardized test preparation (p. 182). To meet these objectives, nursing signature pedagogies place equal emphasis on professional practice, scientific knowledge, and critical thinking.

Signature Pedagogies

On-Site Clinical Training enables nurses to utilize classwork knowledge and hone skills directly on the hospital floor as they care for patients:

Other Nursing Signature Pedagogies Include:

Examples of holistic approaches to professional education can be found in the “Professions” section to Exploring More Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind, eds. Chick, Haynie, Gurung:

CHAPTER 14

“Relational Learning and Active Engagement in Occupational Therapy Professional Education”

by Patricia Schaber, Lauren Marsch, and Kimerly J. Wilcox

Occupational therapy education seeks to foster students who embody “interpersonal sensitivity, empathy, respect for the dignity of each human life, concern for justice, and open-mindedness” (p. 190). Signature pedagogies stress the co-creation of knowledge and learning experiences through an emphasis on relationships, affect, and context.

Signature Pedagogies

Central to preparation in occupational therapy is relational learning, or pedagogy focused on relating to clients and aiding them to meet their everyday needs. This video introduces many of the relational aspects of occupational therapy:

Other Occupational Therapy Signature Pedagogies Include:

- Affective Learning

- Contextualized Learning / Reaching Out

Examples of holistic approaches to professional education can be found in the “Professions” section to Exploring More Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind, eds. Chick, Haynie, Gurung:

CHAPTER 15

“Toward a Comprehensive Signature Pedagogy in Social Work Education”

by La Vonne J. Cornell-Swanson

Professional education for social workers follows three levels of apprenticeship, each with its own learning techniques and outcomes. At each level, the student learns skills while exercising critical and contextual thinking in order to prepare for the variety of issues social workers face in their daily practice.

Signature Pedagogies

During the second apprenticeship in social work education, students practice interviewing one another to gain knowledge and skills for helping future clients. Here is an example of one such interview:

Other Social Work Signature Pedagogies Include:

First Apprenticeship:

- Case Studies

- Strengths Orientation

- Social Constructionism

- Culturally Sensitive Practice

Second Apprenticeship:

- Micro, Mezzo, and Macro Practice Experiences

- Simulated Practice

- Video Studies

- Participation in Public Meetings

Third Apprenticeship:

Examples of holistic approaches to professional education can be found in the “Professions” section to Exploring More Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind, eds. Chick, Haynie, Gurung:

CHAPTER 16

“Toward a Signature Pedagogy in Teacher Education”

by Linda K. Crafton and Peggy Albers

Professional education in teaching must convey the knowledge of how students learn, form the student into the professional identity of a teacher, and instill the ideals of democratic engagement and formation within the classroom. Crafton and Albers also stress the formation of “communities of practice” where novice and experienced teachers continue in conversation towards pedagogical innovation and teaching for democracy (p. 227).

Signature Pedagogies

Central to professional education in teaching is the development of the teacher’s professional identity. How do you match your ideals with your practice as a teacher and how do you live into that role in the classroom? Here is a video introduction to professional identity formation by faculty in Mount Royal University:

Other Signature Pedagogies in Teaching Education Include:

From Novice to Expert

What is the aim of professional signature pedagogies, such as those summarized above? What type of professionals do our professional schools seek to form and what is the arch of that formation?

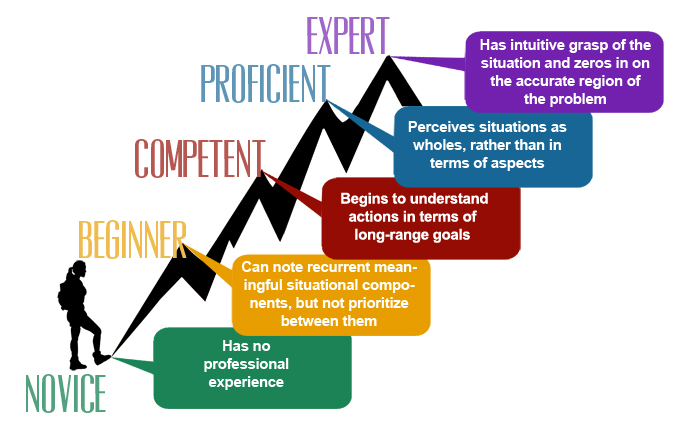

Nursing educator Patricia Benner, working from models developed by applied mathematician Stuart E. Dreyfus and philosopher Hubert Dreyfus, outlines the arch of professional development in nurses as well as pertinent pedagogical approaches based on one’s level of professional development. Her model can then be generalized to other professions, as it has been for clergy professional development by Bonnie Miller-McLemore and Christian Scharen. The following outline and quotes are taken from Benner’s article “From Novice to Expert.” These steps reflect the dynamic interplay between critical thinking and professional practice characteristic of responsible professional education.

Novice: Students with no professional experience

Advanced Beginner: Students with limited on-the-job training who can note “recurrent meaningful situational components, called aspects,” but cannot prioritize between them (p. 403).

Competent: An experienced professional (2-3 years) who can begin to understand actions in terms of long-range goals. The “plan dictates which attributes…are to be considered most important” (p. 404).

Proficient: “The proficient performer perceives situations as wholes, rather than in terms of aspects…Experience teaches the proficient nurse what typical events to expect in a given situation and how to modify plans in response to these events” (p. 405).

Expert: “has an intuitive grasp of the situation and zeros in on the accurate region of the problem without wasteful consideration of a large range of unfruitful possible problem situations” (p. 405).

Pedagogical Needs and Limitations

Novice professional students, due to their limited experience, must use context-free rules to guide their work. However, according to Benner, “Following rules legislates against successful task performance because no rule can tell a novice which tasks are most relevant in a real situation” (p. 403).

“Advanced beginners need help in setting priorities since they operate on general guidelines and are only beginning to perceive recurrent meaningful patterns in their clinical practice” (p. 404). Limited prior experience means advanced beginners tend to treat all aspects as equally important.

Competent professionals need continuing education by decision-making games and simulations that practice planning and coordinating multiple, complex, and contextualized needs or demands. The competent professional can cope and manage many situations but lacks the speed and flexibility of a more advanced practitioner.

“Proficient performers are best taught by use of case studies where their ability to grasp the situation is solicited and taxed. Providing proficient performers with context-free principles and rules will leave them somewhat frustrated and will usually stimulate them to give examples of situations where, clearly, the principle or rule would be contradicted” (p. 405).

Experts still need skilled analytical ability for new situations. “Analytical tools are also necessary when the expert gets a wrong take or a wrong grasp of the situation…When alternative perspectives are not available to the experienced clinician, the only way out of the wrong grasp of the problem is analytical problem solving” (p. 406). Experts can sometimes have trouble describing their decision making process because it spans from a deep, intuitive understanding of the situation.

Conclusion

The developmental arch of a professional student and practitioner moves from strict application of context-free rules to a holistic and intuitive understanding of concrete situations. Throughout the arch, the professional student engages in an ongoing and deep conversation between theory and practice. As Benner puts it, “Theory offers what can be made explicit and formalized, but clinical practice is always more complex and presents many more realities than can be captured by theory alone. Theory, however, guides clinicians and enables them to ask the right questions” (p. 407). Responsible professional pedagogy must teach the dialogue between theory and practice, rather than simply offer a basic skill-set. Thus, professional pedagogy must necessarily include the critical thinking skills of the liberal arts as well as the practical skills necessary to do the job.

This teaching guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.