Creating Accessible Learning Environments

| by Amie Thurber, Joe Bandy, and participants in the 2017-2018 Disability and Learning Learning Community at Vanderbilt University.1 |

| Cite this guide: Thurber, A., & Bandy, J. (2018). Creating Accessible Learning Environments. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved [todaysdate] from http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/creating-accessible-learning-environments/. |

There are estimated to be 50 million people with disabilities in the U.S. today. Disabilities may be temporary, relapsing or remitting, or long-term. Although there are hundreds of distinct kinds of disabilities, we may group them into the following categories: physical disabilities, mental disabilities, and sensory disabilities. Disabilities are complex; they may be a source of stigma or shame and may also be a cherished part of a person’s identity and the basis for meaningful community. The focus of this guide is creating inclusive and accessible higher education classrooms—beyond accommodation—for a range of students with disabilities

This guide is organized around the following sections:

- Framing Access: Theoretical perspectives related to teaching students with disabilities

- Access in Context: Disability Rights Movements and Higher Education

- Disability at Vanderbilt

- Strategies for Creating Accessible Learning Environments

Framing Access: Theoretical perspectives on disability

Issues of accessibility in higher education have been shaped by ongoing theoretical debates. The most prominent perspectives are often described as the ‘medical model’ and the ‘social model’ of disability. Put simply, the medical model tends to focus on addressing the diagnoses of deficiencies and accommodations for a disabled individual, while the social model embraces disability as a difference and focuses on correcting systematic exclusions in institutions based in ableism—discrimination or prejudice against people with disabilities (for more, see Titchkosky, 2011). More recently, a third perspective, referred to as the ‘cultural model,’ has emerged. This model reframes disability as “a valuable form of human variation” (Hamraie, 2016, p. 260) The table below summarizes differences in the three perspectives:

| Medical model | Social Model | Cultural model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| View of disability | A deficiency or abnormality | A difference | Valuable human diversity |

| Cause of | A disability rooted in physical or psychological deficiency | Ableism, lack of accessibility | Ableism, lack of accessibility, attitudinal barriers |

| Locus of problem | The individual | Social institutions and processes | Social institutions and processes; ableist ideology |

| Change agent | Medical or technological expert | Individuals with disabilities, disability advocates, social movements, institutional leadership | Disability culture, social movements, society |

| Target of change effort | Individuals with disabilities and other’s efforts to accommodate | Institutional processes and protocols; social practices; societal norms and values | In addition to changing. Institutions, changing prevailing understandings of disability as a problem |

| Goal of change effort | To diagnose, diminish, correct, and/or accommodate perceived deficits | To increase accessibility in all aspects of society and remove barriers that restrict life choices for disabled people | To reframe disability as a valuable way of being in the world |

Ultimately, these different perspectives on disability—as a problem, a difference, or valuable—inform the way questions of access are approached in higher education settings. Most colleges and universities function within a medical model of disability. Typically, to get an assistive technology or accommodation, disabled students must prove that they have a recently-diagnosed disability. These accommodations treat disability as a deviation from the norm. By contrast, if a university were to adopt a social or cultural perspective on disability, the goal would be to increase accessibility for all students, regardless of whether they have a formal diagnosis. The focus would be on accounting for human variation by design.

|

|

Person first or disability first language?There are ongoing conversations and debates within Disability Studies and the Disability Rights Movement as to whether to use person first (“a person who is deaf”) vs disability first language (“a Deaf person”). Both are responses to deficit-based views of disability. For some, person-first language is an important way to reclaim humanity. For others, the self-identification with disability culture is a meaningful counterpoint to stigmatizing disability. For a reflection on the debate related to person first/disability first language, see this blog post. |

Further reading:

- Titchkosky, Tanya. 2011. The Question of Access: Disability, Space, Meaning. University of Toronto Press.

- Hamraie, A. (2016). Beyond Accommodation: Disability, Feminist Philosophy, and the Design of Everyday Academic Life. philoSOPHIA, 6(2), 259-271.

- Linton, S. (1998). Disability studies/not disability studies. Disability & Society, 13(4), 525-539.

- Miles, A. L., Nishida, A., & Forber-Pratt, A. J. (2017). An open letter to White disability studies and ableist institutions of higher education. Disability Studies Quarterly, 37(3).

- Dunn, D. S., & Andrews, E. E. (2015). Person-first and identity-first language: Developing psychologists’ cultural competence using disability language. American Psychologist, 70(3), 255.

The struggle for access: The Disability Rights Movement, higher education, and the law

The Disability Rights Movement

The Disability Rights Movement has shaped societal expectations regarding accessibility in higher education and the regulatory frameworks to which colleges and universities must comply.

Key historical moments in the Disability Rights Movement are highlighted below.

- 1940s-Disabled workers and veterans organize for recognition, access to the workplace

- 1950s-60s- First university programs for disabled students are established at University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana, University of California, Berkeley, and other campuses.

- 1968-The Architectural Barriers Act requires accessibility in federal buildings. It is not enforced.

- 1970s- The de-institutionalization movement calls for the integration of disabled people into public life and removal from institutional segregation.

- 1973- The first piece of federal legislation protecting people with disabilities was the Federal Rehabilitation Act, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability in federally funded programs, including colleges and universities. Seeks to enforce Architectural Barriers Act.

- 1975- The Education for All Handicapped Children Act—later renamed to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)—guaranteed access to public K-12 education for children with disabilities.

|

|

Transitioning to collegeAlthough the federal government |

- 1975- The Education for All Handicapped Children Act—later renamed to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)—guaranteed access to public K-12 education for children with disabilities.

- 1978- Disability activists stage successful “504 sit-ins” to demand compliance with federal disability rights laws after the Federal Rehabilitation Act is not enforced.

- 1990- The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibiting discrimination on basis of disability in employment, public services, and public accommodation (including many areas of colleges and universities), with the goal of full participation of people with disabilities throughout society.

- 2008- In response to several Supreme Court cases that narrowly interpreted the ADA’s definition of disability, Congress passed the ADA Amendments Act (ADAAA). The purpose of the act is to ensure that the intended beneficiaries of ADA were being appropriately served by the law.

- This timeline was adapted from the Anti-Defamation League, “A Brief History of the Disability Rights Movement.”

- To learn more about ADAPT, a leading organization in the Disability Rights Movement, watch this trailer.

Disability rights and higher education

Today, three sets of laws regulate disability rights in higher education settings:

- Title II of the ADA applies to public colleges that are operated by a state or local government.

- Title III of the ADA applies to private colleges/universities/places of education.[2]

- Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act applies to places of education that receive federal funds.

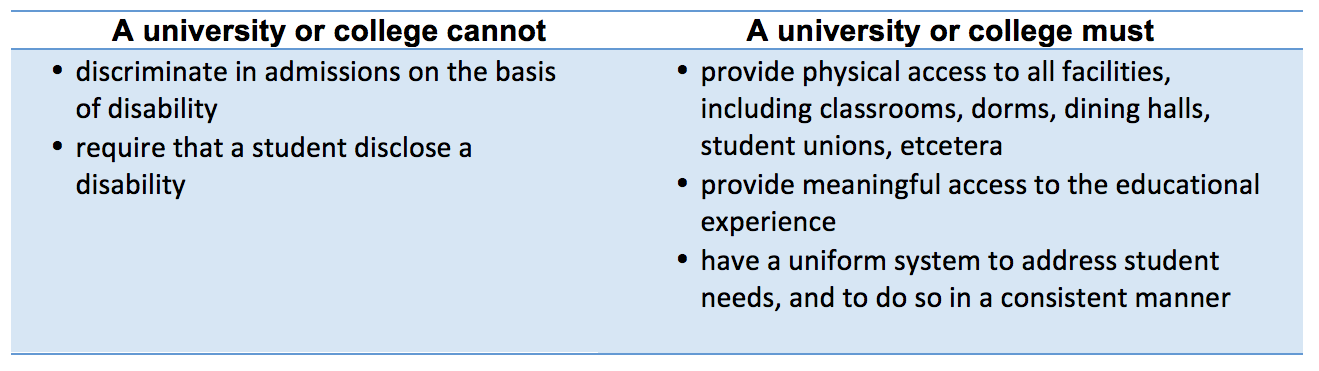

These laws do not require colleges or universities to modify academic requirements considered essential to the curriculum, but they do set minimum expectations, including the following:

Note, what legally constitutes “meaningful access” may not be optimal access for a student. For example, a university may provide meaningful access to a blind student in a biology class by ensuring a readable version of the text is available. However, given the degree that biology relies on visual models, optimal access might include having tactile or 3-D versions of those models, something that may not readily be provided. Further, there is a high level of variability across institutions in the ways they meet these needs, as institutions are differently resourced and differentially prioritize accessibility. Some of the ways higher educational institutions may provide meaningful access include:

- Provision of auxiliary aids or services (i.e. provision of a sign language interpreter or a screen reader).

- Modification to nonessential academic requirements (i.e. allowing a student to complete an exam orally rather than in writing or have additional time to complete exams).

- Reasonable adjustments to policies, procedures or practices (i.e., increasing number of allowable absences, exception to no-pet policy).

Ultimately, ensuring access is not simply an issue of legal compliance, but a reflection of an institution’s commitment to creating educational settings in which all learners can participate, develop, and contribute.

For further reading, see:

- Dolmage, J. (2017). Academic Ableism. Anne Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Hamraie, A. (2016). Beyond Accommodation: Disability, Feminist Philosophy, and the Design of Everyday Academic Life. philoSOPHIA, 6(2), 259-271.

- Price, M.(2011). Mad at School: The Rhetoric of Mental Disability in Higher Education. Anne Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Disability at Vanderbilt

Though many disabilities are unreported, in 2018 there were more than 1000 Vanderbilt students who had registered over 100 different disabilities (out of ~12,000 students). Students with disabilities have several on-campus resources that may offer support.

VU Resources

- Student Access Services: Provides disability services for qualified students. To determine eligibility, students apply for services through the Access Center. Specific documentation criteria and examples of common services can be found on the website.

- Student Ability Alliance: A student-organized and student-led organization that discusses the importance of disability awareness.

- Plant Operations: Responsible for facilities and grounds, Plant Operations is the office to which you may report accessibility concerns, such as:

- inoperable automatic door openers

- inoperable/missing audible crossings

- debris/ice on sidewalks

Working with Students Enrolled through Next Steps

Vanderbilt University is home to Next Steps at Vanderbilt, a 4-year inclusive higher education program committed to providing students with intellectual disability inclusive, transformational postsecondary education in academics, social and career development, and independent living. Students enrolled through Next Steps complete course work with the assistance of academic tutors and customized “Independent Learning Agreement”. To facilitate an authentic college and classroom environment for all, students enrolled through Next Steps are not accompanied by a peer mentor or staff member in the classroom. In addition to the information in this guide, instructors with students enrolled through Next Steps in their classes may benefit from some additional recommendations.

- Hold High Expectations

- Because college was not a viable option for students with intellectual disability until recent years, our students are eager learners with a high-degree of gratitude. Our students want to be a part of Vanderbilt University and a contributing member of a learning environment.

- Our students are first and foremost full-time Vanderbilt students and just as other Vanderbilt students, we hold high expectations for our students in the classroom.

- Students enrolled through Next Steps should be expected to participate in class discussions to the level that they are able, complete their assignments, come prepared and on time to class, and display appropriate college behaviors.

- Look Forward to Reciprocal Benefits

- Hosting a student enrolled through Next Steps is not only beneficial for the student, but equally valuable to his/her classmates. Traditional students are afforded the opportunity to work alongside students with diverse abilities and are exposed to different ways of thinking. Inclusive classrooms equip university students with more knowledge and experience working within a diverse and changing world.

- Adopt Universal Design for Learning Approach

- It is a myth that faculty have to provide extensive modifications because they have an inclusive classroom. However, much of what works well with students enrolled through Next Steps in the classroom, also will work well with traditionally enrolled Vanderbilt students. Refer to the section “Strategies for Creating Accessible Learning Environments” in this guide for details about UDL.

- The main difference in an academic experience for students enrolled through Next Steps and their classmates comes down to the demonstration of knowledge. As a program, we work with our students, peer mentors, and faculty to develop a customized syllabus “Independent Learning Agreement”. The student voice is essential in the development of these agreements.

- We understand many courses offered at Vanderbilt are robust in nature with complex content being taught. Our students have support in grasping the main concepts of the course by partnering with academic tutors and following the customized “Independent Learning Agreement”.

- While our students do not receive traditional grades for their completion of a course, our program consistently evaluates and monitors students’ progress to ensure students are meeting their program of study requirements for graduation.

- Treat All Students Equal in the Classroom

- Faculty should address any issues or challenges that arise just as they would for any other students enrolled in the classroom. It is important to note that our program is equipped to provide support to students and faculty to ensure a successful experience.

Disability History at Vanderbilt

Did you know…there are a number of significant people and initiatives connected to Vanderbilt University that have increased accessibility for people with disabilities?

In 1928, Vanderbilt student Morris Frank became the first known American to be partnered with a guide dog. With assistance from Dorothy Harrison Eustis, an American dog trainer who was training dogs in Switzerland to assist blind WWI veterans, Frank founded The Seeing Eye in Nashville, TN. It was the first guide-dog school in the United States and continues to this day.

The Vanderbilt Kennedy Center (VKC) was founded in 1965 as a research, educational, and advocacy center aimed at making positive differences in the lives of persons with developmental disabilities and their families. In 2016-2017, VKC researchers published 292 publications, provided continuing education to 3100 teachers and care providers, and provided resources to thousands of people with disabilities and their families.

The Peabody Experimental School opened in 1968 with the goal of offering an on-campus research-oriented preschool serving young children with developmental disabilities, children who are at risk for developmental delay, and typically developing children. The school was later renamed the Susan Grey School in honor of a pioneering Peabody educator. It continues to integrate an exceptionally high-quality pre-school for children, teacher training, and early-childhood research, while serving as a demonstration site for early interventions and preschool services for children with disabilities.

Michael Miller was the first Vanderbilt student to map campus accessibility. After graduating in the 1980s, Miller worked at the Student Access Services Center. Today, the testing center is named after him.

In 1994, Sarah Ezell—diagnosed with a rare genetic disorder at birth and given low odds for survival—earned an undergraduate degree at Vanderbilt University in cognitive studies and mathematics before completing a Master of Education in special education, also at Vanderbilt. She had an impressive career in advocacy, helping countless disabled youth and young adults gain access to meaningful opportunities for education, employment, and community.

In 2010, the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center launched Next Steps, a 4-year higher education program committed to providing students with intellectual disabilities inclusive, transformational postsecondary education in academics, social and career development, and independent living. Since opening, 33 students have earned a certificate from Next Steps at Vanderbilt and 87 percent have had employment at graduation.

Following faculty research to map campus accessibility in 2014-2016, Vanderbilt University began its first Accessibility master plan in 2017, which identifies and addresses accessibility priorities for the campus and its classrooms.

Despite these accomplishments, Vanderbilt University—like many educational institutions—still has work to do to increase accessibility. For one student’s reflection, see this 2017 editorial published in The Washington Post.

Strategies for Creating Accessible Learning Environments

Although Vanderbilt University encourages all students with disabilities who desire reasonable accommodations to seek services through Student Access Services, faculty have an essential role to play in making courses accessible and creating a climate of equity and inclusion. While individual needs are difficult to anticipate, there are many things professors can do to create inclusive and accessible environments for a wide diversity of learners. This guide reviews strategies in the following areas:

- Communication with students

- Physical spaces of learning

- Course materials

- Classroom climate

- Out of class activities

Most of the strategies highlighted in these sections reflect the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL). UDL is an educational framework that emphasizes the use of flexible goals, methods, materials, and assessments in order to provide effective instruction to a diversity of learners. Rather than approaching accessibility as an afterthought or only on a case-by-case basis, UDL principles help instructors to design courses that address the needs of diverse learners from the start so that all students may benefit. For example, a note-taker is a common accommodation given to students with disabilities, however, in note-heavy classes, this may be beneficial to many students. Some instructors rotate the role of note-taker throughout the class as a way of creating a shared set of notes that all students can access.

Note, the strategies suggested in this guide are not exhaustive. For more recommendations, see:

- Dolmage, J. (2015). Universal design: Places to start. Disability Studies Quarterly, 35(2).

- Checklist for Course Accessibility

Communication with Students

Creating open lines of communication with your students is essential. There are a variety of ways instructors can build a foundation for open communication:

- Consider adding an “Inclusive Learning Statement” to your syllabus. Tulane University’s Accessible Syllabus website offers the following example: “Your success in this class is important to me. We will all need accommodations because we all learn differently. If there are aspects of this course that prevent you from learning or exclude you, please let me know as soon as possible. Together we’ll develop strategies to meet both your needs and the requirements of the course. I encourage you to visit the Office of Disability Services to determine how you could improve your learning as well. If you need official accommodations, you have a right to have these met. There are also a range of resources on campus, including the Writing Center, Tutoring Center, and Academic Advising Center.” Reiterate your desire to help all students succeed by communicating a version of this statement aloud in the first week of class.

- Note, the Accessible Syllabus website has many other helpful recommendations to create an accessible syllabus, including information on formatting, text, images, rhetoric, and other course policies.

- When you receive notification from your campus disability services office that a student has requested accommodations in your course, reach out to the student individually, in private, to discuss how accommodations may work best for them. A student’s disclosure of a disability is always voluntary and some students may feel nervous to disclose sensitive medical information to an instructor. Whether or not a student discloses details of their disability, you can discuss appropriate accommodations. In some cases, accommodations may be straight forward – such as providing an alternative testing location. Other situations may require ongoing brainstorming between the instructor and student. It can be helpful for an instructor to describe upcoming activities or assignments (particularly those not fully described in the syllabus) and ask the student what, if any, additional accommodations may be needed. As the course proceeds, it is helpful to check in with the student periodically. Not all needs can be anticipated in advance, and given the nature of some disabilities, needs may change over the course of a term. Ask the student, “How are the accommodations we have implemented working for you? Is there anything we should consider changing?”

- When you make announcements in class, for example regarding changes in due dates or room locations, make sure to always send them in an email or online announcement as well.

- Consider your course policies in the interest of creating an inclusive classroom environment. For example, do you have a no laptop policy in your classroom? If so, how might that negatively impact students with disabilities?

- For more of this topic, see the recent essay by Katie Rose Guest Pryal “When you talk about banning laptops, you throw disabled students under the bus”

Physical learning spaces

Ensuring physical accessibility includes consideration of the building location, the classroom location (within a building), as well as the layout of the classroom, and classroom technologies (i.e. lighting, tables, seating, projection, white boards). When considering the physical accessibility of your class, keep in mind:

- Changes in weather or campus activities can disproportionately impact students with mobility impairments. For example, sidewalks may be impassable due to snow or ice, piles of yard debris during landscaping, or equipment in place for a campus event. These may delay students or may present such a barrier that a student may need to participate remotely. As a best practice, if you notice an area that is inaccessible on campus (which also includes inoperable lifts, elevators, or audible crossings at crosswalks), let the plant operations department know immediately.

- To the greatest extent possible, set up your classroom so that students with wheelchairs or service dogs have room to navigate into and around the class. For example, if the classroom is set up with workstations, consider leaving an open spot—without a chair—at multiple tables.

- Engage your students in thinking about accessibility in your classroom. Some rooms may not have any moveable furniture, but present options in terms of lighting, sound, or size of text on presentation materials. Other rooms may be highly adaptable.

- Moving classes at the last minute and changing classroom layouts can cause difficulty for a range of students, including those with mobility, sight, or hearing impairments, as well as people with anxiety. For example, students using guide dogs may spend up to a month before classes begin training their guide dog to navigate them to class, and to a particular seat within the class. Whenever possible, alert students in advance as to changes of location or room set up.

Course materials

Ensuring accessibility of course materials includes consideration of 1) the course management system (i.e. Brightspace, Blackboard, etc.); 2) assigned reading materials, handouts, and presentations; and 3) audio or video used in class. Creating accessible materials takes time. It can necessitate learning new technologies and being creative when considering alternative ways to share information, and/or allow students to participate in class.

1. Course Management Systems

Many course management systems have built in accessibility features. For example, Brightspace (Desire2Learn) has screen reader accessibility features, keyboard-online navigation features, screen magnifiers, and design features to assist both students and instructors. To learn how to make your content more accessible to individuals who use screen readers or screen magnifiers, as well as individuals with colorblindness, click the “Check Accessibility” button in the bottom toolbar. This will provide you with warnings and ways to improve accessibility.

For those using other course management systems, please check with their helpdesk or campus consultants. Ultimately, it is an instructor’s responsibility to get to know the accessibility features and limitations of their institution’s course management system, and to take advantage of the tools that will allow their students to fully participate.

2. Course reading, handouts and presentation materials

It is important to make your syllabus and course materials available to students as soon as possible, so students who may need more time can begin accessing materials. The most common strategy for increasing accessibility of course texts (which include any assigned readings, presentations, and handouts) is providing versions that are readable, especially by screen readers. Most computers come equipped with a screen reader technology, which essentially converts printed text into auditory words to which the user can listen. For this technology to work, reading materials must be saved in a text file, such as a Word Document or Rich Text Format (RTF). Converting materials from PDF or PPT to readable text increases accessibility to a wide variety of learners, including people with learning disabilities, literacy difficulties, visual impairments, or people who multitask. You may find some readable text versions of your course materials are already available. In other cases, you may need to prepare them.

- Quick Tip Sheet for creating accessible materials

Importantly, text-reading-technology does have limitations. If there are graphics that are critical to the course materials (i.e. tables, graphs, or other images), you will need to find another way to share these with students who have sight impairments, for example by explaining figures in prose form, transferring the graphic onto a tactile surface, or creating a 3-D model of the figure.

Further reading: This 2018 special issue of Learned Publishing focuses on accessibility in publishing.

3. Audio & Video

Instructors increasingly utilize audio and video materials in class. Captions and descriptions are required by law (Section 508) to support students with disabilities, though as described below may benefit a wide range of learners. There are two types of technologies to increase accessibility to audio and video.

Converting audio (or audio portions of video) to text (e.g., closed captioning) can be done through computer-assisted-programs. Captioning video increases accessibility to a wide variety of learners, including people with learning disabilities, literacy difficulties, hearing impairments, or second language learners.

Creating audio descriptions of visual images is typically needs to be done by a person in real-time, or through use of a pre-recorded narrative. Audio descriptions of video increases accessibility to a wide variety of learners, including people with learning disabilities, literacy difficulties, and visual impairments.

- Quick Tip Sheet for creating accessible materials

Classroom Climate

Students learn best when they feel respected, included, and that instructors are invested in their development. Students with disabilities can experience stigma, marginalization, and negative stereotypes from their peers and instructors. In Barbara Davis’s Tools for Teaching, she explains that it is important for instructors to “become aware of any biases and stereotypes [they] may have absorbed…Your attitudes and values not only influence the attitudes and values of your students, but they can affect the way you teach, particularly your assumptions about students…which can lead to unequal learning outcomes for those in your classes” (2010, p. 58).

Strategies for creating an inclusive and welcoming classroom climate include:

- Pay attention to your engagement with students. In courses where teacher/student ratio allows, endeavor to learn and use students’ names. Use classroom engagement strategies that allow students to contribute in a variety of ways, for example, through online discussion boards, in-class discussions, and individual assignments.

- Pay attention to and enable group interactions in the classroom. Use peer-to-peer engagement strategies that facilitate relationship-building, trust, and the creation of a learning community within the class.

- Respond to microaggressions in the classroom. People with disabilities experience a multitude of everyday comments and behaviors that, while not intended to be hurtful, nonetheless can be stigmatizing, marginalizing, and/ or dehumanizing. Microaggressions ultimately communicate implicit assumptions and prejudices that can injure the targeted group, alienating them from their peers and the learning community faculty attempt to create. For instance, here are some microaggressions and the implicit biases they communicate:

| Comment | Implicit Code |

|---|---|

| “I don’t know how you do it – I’d hate to be like you” | Your disability is not comprehensible and is always a deficiency. |

| “You look so normal” | Your disability is not normal, and you hide it well. |

| “You are so inspiring.” | Your disability defines you; you are deficient; and you are here for my inspiration.3 |

It is important for instructors to be attentive to microaggressions in the classroom, to normalize inclusive and appropriate language, and to consider effective strategies for turning difficult dialogues into teachable moments.

Out of Class Activities

Not all learning happens in the classroom. Does your course integrate lab work, field work, practicum placements, internships, service learning, or presentations in community based or academic settings? If so, it will be important to think about accessibility within these spaces as well. The Ohio State University’s Composing Access website offers helpful guidelines for creating accessible events.

Conclusion

As Dr. Aimi Hamraie writes, “Meaningful access requires collective labor” (2016, p.266). The Center for Teaching is committed to partnering with students and instructors to increase accessibility of learning experiences at Vanderbilt University. Contact us for more information or assistance.

[1] Each year, the Center for Teaching offers a number of topic-based Learning Communities intended for members of Vanderbilt’s teaching community interested in meeting over time to develop deeper understandings and richer practices around particular teaching and learning topics. In 2017-18, the CFT was proud to host a year-long learning community on disability that explored principles of inclusive teaching, universal design for learning, instructional accommodations, as well as legal and cultural issues relevant to students and faculty with disabilities. This guide reflects a summary of the topics explored over the five-part series. This guide is an update to the Teaching Students with Disabilities guide developed by Danielle Picard.

[2] Note, ADA Title III offers an exception for “religious organizations or entities controlled by religious organizations, including places of worship.” However, given that the Rehabilitation Act does not provide a religious exception, in practice the vast majority of higher education entities are regulated by one of these three sets of laws.

[3] For more on the problematic ways in which disabled people are regarded as inspiration, see Stella Young, “I’m not your inspiration, thank you very much.” TED talk

This teaching guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.