Blogs and Discussion Boards

This teaching guide has been retired. Visit our newly revised guide on this topic,

Teaching with Blogs

- Introduction

- Student Expectations

- Why Use a Blog?

- Getting Started Blogging at Vanderbilt

- Common Questions

- Discussion Boards

- Additional Resources

Introduction

Many instructors are using online writing – email, asynchronous threaded discussion groups, and synchronous chat – in their teaching. And both students and teachers are using online communications to maintain personal and business relationships. Here we present a set of guidelines faculty who are just beginning to use these technologies in teaching.

- Build the online writing component into the grading structure . It’s not just that students will spend time on something if they know that a grade depends on it. It’s also that the assignment of a grade indicates to them that it’s important.

- Acknowledge the time that will be spent on it . Adding a significant online writing component is adding to the course load – on your students and on you. If you value it, and if you want your students to value it, then decide what other elements of the course will be dropped to make room for it.

- Establish a clear and compelling relationship between the online writing and other elements of the course . Think of the online writing environment as another environment in which students encounter each other and you. Make clear to your students how you expect the work in this online environment to build upon and contribute to the other work in the course.

Student Expectations

In general, students have grown up surrounded by digital technologies and are comfortable integrating them into daily life in ways that most people of the previous generation are not. Marc Prensky coined the term “digital natives,” to represent the digitally enabled generation that now sits in our classrooms, and to contrast them with the rest of us who are “digital immigrants.” While as a generalization the distinction between digital natives and digital immigrants is accurate, it is important to recognize that not all of your students will have experience using and be comfortable with these new digital technologies. As with anything else, be aware of what skills and abilities your students bring to the classroom and adapt the learning environment accordingly.

The annual Educause Center for Applied Research (ECAR) study of undergraduate students helps to shed light on how technology affects the college experience. The 2011 study gathered responses from a nationally representative sample of 3,000 students in 1,179 colleges and universities.

Some conclusions ECAR has drawn from the latest survey are:

- Facebook generation students juggle personal and academic interactions

- Students prefer, and say they learn more in, classes with online components

- Students are drawn to hot technologies, but they rely on more traditional devices

- Students report technology delivers major academic benefits

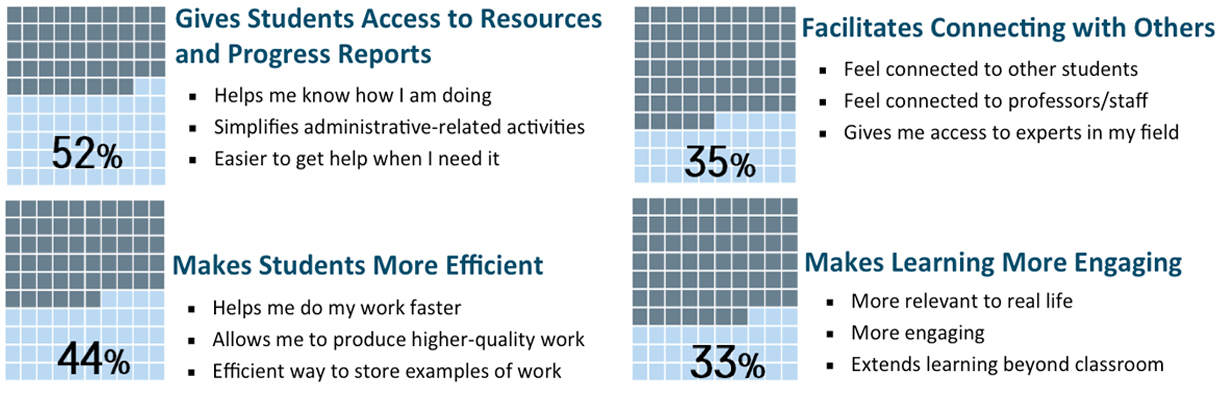

The survey also reported that students identified these four technology factors that support academic success.

Blogs are just one of many technologies that can help facilitate these four factors of academic success. They are part of what Randall Bass and Heidi Elmendorf, of Georgetown University, call “social pedagogies.” They define these as “design approaches for teaching and learning that engage students with what we might call an ‘authentic audience’ (other than the teacher), where the representation of knowledge for an audience is absolutely central to the construction of knowledge in a course.” You can learn more about social pedagogies in the Chronical article, “A Social Network Can Be a Learning Network” by Derek Bruff.

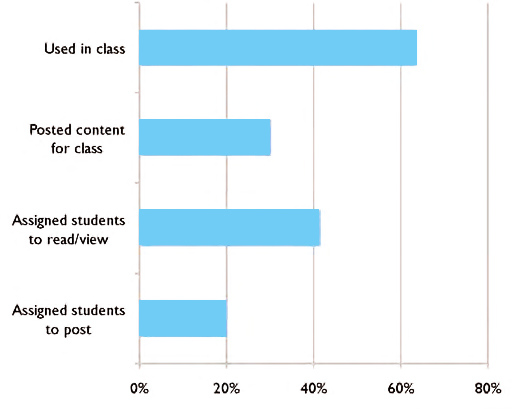

According to a survey of over 1,900 higher education faculty conducted by the Babson Survey Research Group and Pearson, Over 40% of faculty surveyed have assigned students to read or view social media as part of course assignments, and 20% have assigned students to comment on or post to social media sites. And in total, 80% of faculty report using social media for some aspect of a course they are teaching.

Some of the general findings from the faculty report include:

- More than three-quarters of all faculty visited a social media site within the past month for personal use, and nearly one-half posted some content during that period.

- Faculty with more than 20 years of teaching experience are less likely to visit and less likely to post than are faculty with less than five years of teaching experience.

- Nearly two-thirds of faculty have used social media in their courses— either during class or as part of an assignment— and those who teach online are more likely to do so.

Read more about how Vanderbilt faculty are increasingly incorporating social media into their classes in this recent Inside Vandy article: “Academic Blogging on the Rise.”

Why Use a Blog?

In “7 Things You Should Know about Blogs,” Educause describes blogs as:

An online collection of personal commentary and links. Blogs can be viewed as online journals to which others can respond that are as simple to use as e-mail. The simplicity of creating and maintaining blogs means they can rapidly lead to open discussions. Faculty are using blogs to express their opinions, promote dialogue in their disciplines, and support teaching and learning; students increasingly use blogs for personal expression and as course requirements.

Essentially, a blog is a personal journal published on the web consisting of discrete entries (“posts”) typically displayed in reverse chronological order so the most recent post appears first. Blogs are usually written by one individual (though occasionally by a small group) and are often themed on a single subject. Many blogs provide commentary and some function as diaries; both types typically combine words, images and links to other online information. An important part of a post is the ability for readers to leave a comment.

Essentially, a blog is a personal journal published on the web consisting of discrete entries (“posts”) typically displayed in reverse chronological order so the most recent post appears first. Blogs are usually written by one individual (though occasionally by a small group) and are often themed on a single subject. Many blogs provide commentary and some function as diaries; both types typically combine words, images and links to other online information. An important part of a post is the ability for readers to leave a comment.

When to use a blog

Blogging can be incorporated into the classroom in many different ways. Here are some of the most common:

- Create a course blog in which you (as the instructor) blogs the content and ask students to comment on your posts before class. You can then use the blog post as a discussion starter. For instance, did someone have an insightful comment? Did you repeatedly see the same question popping up? Share these (and the blog post) to get class conversations started.

- Create a group blog for the students in your course. Via the blog, students will be able to ideas from class, share resources with one another, and draw in outside participants (if you allow them to).

- Require each student to set-up and maintain his or her own blog. This can be a great way to facilitate student journaling, with journal entries either kept private, shared with just the instructor, or shared more widely.

- Individual blogs can be used to scaffold a project or paper. For instance, Post 1 could be a list of potential topics; post 2, 2-3 primary sources on a chosen topic; post 3, a research proposal; post 4, a progress report; post 5, a draft of a section of the paper. The benefit of having students do this on a blog is that you can put them into peer editing groups and students can give one another feedback online.

- Create a course blog that serves as a ‘hub’ which aggregates individual student blogs into one centralized space. On this blog, you could also provide course information such as the syllabus, the schedule, posts about assignments, handouts, and course discussions.

Curious about how instructors are using blogs in their courses?

Here are some examples:

- American Postmodernism taught by Mark Samples at George Mason University: Samples uses a blog in this course to encourage reflections on course readings. Students are asked to contribute weekly and he asks that his students “consider the reading in relation to its historical or theoretical context; write about an aspect of the day’s reading that you don’t understand, or something that jars you; formulate an insightful question or two about the reading and then attempt to answer your own questions; or respond to another student’s post, building upon it, disagreeing with it, or re-thinking it.” For a listing of all of Samples’ course blogs, go here.

- History of American Technology and Culture taught by Jeffrey McClurken at University of Mary Washington: McClurken uses a blog in this course to showcase digital projects by students in the course.

- Archaeology students at Michigan State University: Students in the Campus Archaeology Field School use a blog to engage the public with their excavations.

- Bears in the Sea is a Baylor University blog that documents the experiences of students and faculty as they participate in the HHMI SEA (Strategic Education Alliance) by implementing a creative new laboratory experience for students taking introductory biology.

- Lewis and Clark Around the World is a collaboration between the Department of Overseas & Off-Campus Programs and Watzek Library at Lewis & Clark College. In addition to providing a window into LC Overseas experiences, the site serves as a discussion tool for the group during their time abroad. Program leaders can identify themes for study and assign projects to students. Students then post photos and descriptive analyses to meet these assignments. The group can then convene and discuss what they have posted.

Get Started Blogging at Vanderbilt

Vanderbilt has a well-supported blogging service that uses WordPress as its platform. It’s easy to set up your site. Visit the Vanderbilt University Web Communications website and click on the Start a New Project button. You’ll be asked to log on using your VUNet ID/Passoword credentials to access new site request form. If you are affiliated with the College and Arts and Science, please contact Rob Fuller about your project. If you are with a VU Medical Center office, lab or department, contact the VUMC Web Development team.

University Web Communications also offers monthly training sessions to help you learn how to use WordPress.

Common Questions About Online Discussions

How do I evaluate a student’s work? There are a few strategies you can use to make grading online discussions easier:

1. Grade every entry using a simple rubric. This one, by Mark Sample of George Mason University, is so simple that after some use you’ll be able to quickly grade any given blog post:

Five-point rubric, ranging from 0 (no credit) to 4 (exceptional)

| Rating | |

| 4 | Exceptional. The journal entry is focused and coherently integrates examples with explanations or analysis. The entry demonstrates awareness of its own limitations or implications, and it considers multiple perspectives when appropriate. The entry reflects in-depth engagement with the topic. |

| 3 | Satisfactory. The journal entry is reasonably focused, and explanations or analysis are mostly based on examples or other evidence. Fewer connections are made between ideas, and though new insights are offered, they are not fully developed. The entry reflects moderate engagement with the topic. |

| 2 | Underdeveloped. The journal entry is mostly description or summary, without consideration of alternative perspectives, and few connections are made between ideas. The entry reflects passing engagement with the topic. |

| 1 | Limited. The journal entry is unfocused, or simply rehashes previous comments, and displays no evidence of student engagement with the topic. |

| 0 | No Credit. The journal entry is missing or consists of one or two disconnected sentences. |

2. Grade selected posts using a broader rubric. You can select the posts yourself or ask students to select 3-5 of their ‘best’ posts for evaluation. You can take a look at existing rubrics (like this one or this one) and adapt one to fit your needs.

- Regardless of which assessment method you choose, you’ll also want to:

- Discuss blogging with your students and establish criteria for what makes a ‘good’ post. Consider developing a few ‘model’ posts that your students can use to get an idea of what you’re looking for.

- Provide feedback to students about their blog or discussion board entries. This feedback can take the form of actual grades or positive/negative comments on blog posts that indicate questions or concerns you may have.

- Highlight particularly good blog posts (and comments) in class and on your blog.

How do I incorporate the blog into class time? Some suggestions include:

- Display posts on the projector during class, and refer to posts as you lecture. Particularly if you noted common themes arising in your students’ posts or comments.

- Encourage students to be creative and include video or music or other media that relates to the topic in their blog posts. You can then play clips in class.

You can read more about grading blogs in the Chronicle article “‘How are you going to grade this?’: Evaluating Classroom Blogs” by Jeff McClurken and Julie Meloni.

How private or public should my blog or discussion board be?

Issues around privacy, intellectual property, and audience will need to be considered when creating your blog. You’ll need to decide if the blog should be limited to only the students in your class or be made public. Sometimes making a blog public helps to raise the stakes for the students, knowing that anyone could read their work. On the other hand, it might also create a situation that hampers frank and honest course discussions. You’ll have to weigh these benefits/drawbacks when creating a blog for your class.

Some good advice on how to approach these questions can be found in the HASTAC article “Should Class Blogs Be Private or Public?” by Cathy Davidson, Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies at Duke.

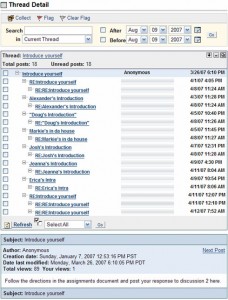

Discussion Boards

Similar to a blog, a discussion board allows multiple people to respond to comments and questions. They are threaded, in that one in a response to a particular message is nested under the message to which it is a response. Replies that are associated with the same post are grouped together, creating message threads that can be expanded and collapsed. The nesting is usually indicated in the online environment by indentation, much as the organization of major and minor points is indicated in a formal outline by indentation.

Similar to a blog, a discussion board allows multiple people to respond to comments and questions. They are threaded, in that one in a response to a particular message is nested under the message to which it is a response. Replies that are associated with the same post are grouped together, creating message threads that can be expanded and collapsed. The nesting is usually indicated in the online environment by indentation, much as the organization of major and minor points is indicated in a formal outline by indentation.

- Decide whether students will be allowed to initiate threads . Some faculty prefer to set the context for each discussion, whether the discussion is face-to-face or online. Others allow students to initiate discussions in one or both environments.

- Is the threaded discussion a repository for course knowledge or a forum for student exploration? Can students expect that you will correct misconceptions that surface in the discussion?

- Make clear to students the terms on which you will participate in the online discussion . Will you be an active participant, committed to reading every post by every student? Or will you read only some of the posts? If you post, should students read your posts as decisive statements on the topics or as exploratory and questioning prompts?

- How will student posts be evaluated? If you are evaluating student postings to the online discussions, by what criteria will you be evaluating them?

- Read and evaluate a student-selected portfolio of postings rather than reading all of the postings . Including the online discussion in the grading rubric of the course doesn’t require reading and grading every student’s every posting. Instead, ask students to assemble a portfolio of postings at the end of the semester and comment on these postings. A student might be asked to comment on three different postings she made during the semester. Or she might be asked to comment on a particular exchange in which she participated. Your evaluation can then be multi-layered, considering the posts themselves, her decision to select the particular posts she selects, and her commentary on them.

- Structure the requirements for posting so that there is a critical mass of participation early in the course . Just as a class that emphasizes discussion will succeed for students only if they come to class, an online discussion will succeed only if students log in. Similarly, just as it’s important to establish the expectations of such face-to-face discussion early in the semester, it’s important to establish similar expectations in the online environment.

- Build in connections between online and face-to-face discussion . Consider assigning students the task of developing more fully in the online environment a point that was introduced in the face-to-face discussion. Even if you require only a small number of students to do this each week, their postings will constitute a critical mass that will entice others who aren’t required to post that week to visit the discussion to see what they might learn. Similarly, if you regularly introduce points in the face-to-face discussion that you read in the online discussion, this will demonstrate to students that you find that discussion valuable.

Additional Resources

-

Teaching with Blogs: The Center for Humane Arts, Letters and Social Sciences Online

-

Lessons from a First Time Course Blogger is a blog site created by a faculty member at The Bernard L. Schwartz Communication Institute at Baruch College that chronicles her experiences as a novice blogger.

- Gardner Campbell, Director of Professional Development and Innovative Initiatives in the Division of Learning Technologies and Associate Professor of English at Virginia Tech, maintains an active educational technology blog. Read his blog post Blogs and Baobabs to learn more about how he uses blogging.

- So you’re thinking of blogging?: A blog posting about getting started with blogs in education, comparing four popular blogging platforms.

- UMW Blogs is a publishing platform available to any member of the University of Mary Washington community. Based on WordPress, it allows any faculty member, student, or staff employee to create a blog, a course or project site, or professional Web presence.

This teaching guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.