Sustainability Across the Curriculum

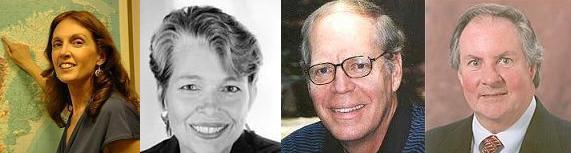

On March 30, the CFT hosted a Conversation on Teaching on the topic of “Sustainability Across the Curriculum.” A diverse group of faculty panelists offered perspectives from across the disciplines.

Jack Barkenbus, an Associate Director of the Climate Change Research Network and a researcher at the Vanderbilt Institute for Energy and Environment, began the conversation. In addition to his work at Vanderbilt, Barkenbus is the Executive Director of the Tennessee Higher Education Sustainability Association (THESA), an organization committed to supporting sustainability efforts at colleges and universities across the state. Sustainability, Barkenbus argued, is a value that articulates well with the educational mission of the university. He reminded us that civic leadership is a key component of that mission; universities are role models for the community. This is particularly true at Vanderbilt, a premier educational institution and the second largest employer in the state of Tennessee.

Noting that university administrators have sometimes been reluctant to embrace sustainability out of a resistance to its perceived faddishness, Barkenbus argued that we are witnessing a more enduring shift in cultural values. The sustainability movement, he argued, is in the “Kittyhawk” stage of its development; we are in the first years of a new era. Barkenbus pointed out that colleges and universities are encountering a new generation of students, who count sustainability efforts among their top reasons for choosing a school and who are savvy in their appraisal of these efforts. As schools compete for the best students, those students are swayed by the depth and breadth of sustainability programming at different institutions. And given the sluggishness with which many administrations have responded to this cultural shift, sustainability initiatives on campus are more often than not led by students.

Barkenbus discussed two possible models for incorporating sustainability into the curriculum. One model, which has been adopted by many colleges and universities since the 1970s, houses sustainability within a particular discipline or within an interdisciplinary program, such as Environmental Studies. While this approach does engage with practices and principles of sustainability, it also has the potential to relegate sustainability to a limited sphere of influence. The other model understands sustainability as a core educational value, one that ought to find its way into courses “across” the disciplines. This model has the potential to truly transform the university.

Barkenbus highlighted the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE) as an important organization promoting this transformative vision of sustainability, and he pointed to the bottom-up approach to incorporating sustainability across the curriculum modeled by the Ponderosa Project at Northern Arizona State University, and adapted successfully at several other institutions, including Emory, Auburn, and the University of Maryland. These programs offer a two-day intensive faculty workshop with the primary goals of resource sharing, networking, and capacity building for instructors who are developing units or courses around sustainability issues. As programs like these generate momentum at the level of the faculty and curriculum, they will further energize students, and administrations will eventually get on board.

Cecelia Tichi, William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of English, spoke second. Over the past decade, her courses and research have focused on civic engagement and the writers who summon us to it, from the certified literary to investigative journalists. Tichi has taught courses related to sustainability in both the English Department and the Program in American Studies. In particular, she has co-taught several resource-based courses in American Studies with Alice Randall, including courses on coal, food, and an upcoming course on water. In these courses, Tichi and Randall have used portfolio projects as a tool for bringing outside knowledge into the classroom. These projects allow students to become experts on a relevant topic of their choice over the course of the semester, and the portfolio format help to facilitate both the accumulation and the sharing of knowledge, while keeping the focus on process as much as product.

As we come to recognize sustainability as a keyword for the 21st century, Tichi suggested, we must expand the scope of our definition beyond just the environment. We cannot, she asserted, allow ourselves to become “satisfied with recycling bins.” In thinking about sustainability, we must turn a critical lens towards our social infrastructure – focusing on the built environment as much as the non-human natural world. Emphasizing the social justice dimensions of sustainability, Tichi argued that the courses we design should pay particular attention to complex issues such as food security and prison reform. What does it mean, for example, to talk about the concept of sustainability with regard to prisons? Are prisons something that we want to sustain as a society? Educating students to become engaged citizens involves attending to the ethical dimensions of the technologies we use and the investments that we make, both as a society and as individuals.

Jim Clarke, Professor of the Practice in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, spoke third, offering a risk analysis perspective on sustainability in terms of nuclear waste management. Nuclear technology is a particularly vexed issue with regard to sustainability, and this controversy has taken on new contours with the importance of developing carbon-free technologies in the face of climate change. What does sustainability mean in the context of waste, particularly nuclear waste? Clarke pointed to the field of “legacy management” – the management of contaminants that remain hazardous for thousands, even millions of years – as an important sphere for considerations of sustainability. With regard to management, Clarke argued, the question is, how do we make decisions that do not compromise the people that come behind us? The answers require thoughtful planning for long-term maintenance and monitoring, and include regular performance assessments. Even in waste management, Clarke noted, there has been an increasing shift toward a more ecological approach, working toward waste containment systems that integrate with the ecology of a region rather than resisting that ecology. The site specificity of Clarke’s approach to these issues suggests the importance of both place-based and problem-based learning as key components of sustainability pedagogy.

Finally, Beth Conklin, Professor of Anthropology, offered her insights, having taught courses related to sustainability at both the undergraduate and the graduate levels. Conklin pointed out benefits to teaching courses on these issues – dealing with problems and ideas that have current relevance, these courses engage students because of the salience of their personal connections to the issues. At the same time, these courses require a special kind of humility, openness, and flexibility on the part of the instructor. Teaching sustainability issues often involves working with new information, working outside your own field, and teaching students who bring expertise from diverse disciplinary backgrounds. These factors, Conklin suggested, argue for a less hierarchical model for classroom instruction; in teaching these courses, instructors should strive to facilitate collaborative “learning communities.”

Conklin pointed out that because of the contemporary nature of these issues, much of the information related to sustainability comes from journalism, and she argued for the importance of teaching students to become critical consumers of news media. She also identified differences between graduate students and undergraduates who enroll in these courses. Graduate students have a more specialized background, and so tend to come to the course looking for a particular kind of information, which can cause them to skimp on common readings in favor of personal research. Undergraduates, on the other hand, tend to approach these courses as curious and intelligent generalists, and they come to learn content. In both cases, Conklin noted, it can sometimes be difficult to move students away from personal issues and to refocus their attention on analysis of larger social structures. An important part of teaching these issues, then, involves modeling a level of dispassion necessary for critical thought.

The post-panel discussion raised important questions. Several participants were interested to think more about the affective dimensions of sustainability – how, for instance, do we convey the seriousness of contemporary environmental and social problems without making students feel guilt for their complicity with forms of structural violence, without making them feel despair in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds? Reframing the issue, one panelist suggested that in our reconstructive engagement with sustainability issues, we must recognize that we will be living with vast contradictions for the next quarter century or more. Others suggested using personal anecdotes as a way of normalizing the difficulties of achieving a sustainable lifestyle. As more ideas emerged, the discussion moved towards empowering students to become change agents within the university and the community – helping students to recognize the constraints of the structures they find themselves within, generating alternatives, and activating them to change those structures. In the face of our own difficulties as instructors, we should remember that the seriousness of these problems can motivate students as often as it generates apathy.

Technological highlights of the conversation included Computer Science Professor Doug Fisher’s participation via polycom from Washington DC, and CFT Assistant Director Derek Bruff’s live-tweeting of the conversation. In case you missed the conversation, we’ve recorded the panelists’ comments as an audio file, which will soon be available on the CFT website as a podcast. In addition, the CFT is developing a web-based teaching guide on sustainability and ecological pedagogy, which will be available on our resources page in early May.

Submitted by: John Morrell, Graduate Teaching Fellow at the Center for Teaching

Leave a Response