Getting to Know Coursera: Video Discussions

By Katie McEwen, Graduate Assistant

Last time, we began our discussion of some of the shared features in Coursera — across courses and disciplines — with the favored method of presentation: the video lecture. Today, we’ll take a look at a less common approach, the video discussion.

To me, a student and teacher used to small classrooms and plenty of interaction, the video discussions were a return to familiar territory. Finally, a class I could recognize!

Like the in-class lecture footage we introduced in our last post, video discussions require filmed “live” interaction. As a result, this format not only presents information to students, but also models the kinds of discussions of ideas, texts, and contexts found in a discussion-focused seminar.

However, we should keep in mind that these interactions are no less staged than the screencast lectures. Discussions are carefully choreographed and edited to fit within the 8- to 15-minute “chunks” recommended by Coursera. The result: neat, contained, and well paced discussions that bear only a glancing resemblance to the sometimes messy reality of a seminar course.

Certainly, the video discussions present an ideal scenario: universally engaged students, who are articulate, interested, prepared, and always on task. There is not a missing book, lame excuse, or sheepish look to be found on film. In fact, students are often not your usual undergraduates, but rather course TAs or recent majors. Obviously, this improves the quality of discussion greatly, enabling a degree of focus and concise, critical insight difficult to achieve in a spontaneous classroom setting.

Perhaps this is why video discussions often forgo embedded quiz questions. The material, in general, lends itself less readily to the kind of “check-in” questions that test the short-term retention of facts. Instead, video discussions (again, ideally) favor the elaboration of more complex ideas.

The format of video discussions varies by course. Let’s look more closely at a few examples.

In “Modern and Contemporary American Poetry,” Penn professor of English Al Filreis facilitates what he calls “collective close readings” of individual poems. The videos focus on students — here, course TAs and recent graduates from the English Department — as they together work through aspects of a poem. As a Germanist, close reading is a familiar language; I find the discussions fast-paced, thought-provoking, and always engaging, the students terrifyingly articulate.

“Listening to World Music” takes a different approach. Although the course features screencast lectures by the professor — Carol Muller, also at Penn — each weekly unit also includes pre-recorded discussions among the course TAs. These discussions model the comparative listening exercises students are asked to complete and guide them through questions to consider when listening to piece of music.

Video discussions, called “Global Dialogues,” also supplement the weekly screencast lectures in “A History of the World since 1300.” In this course, however, discussions function more as a “panel of experts,” where the professor, Jeremy Adelman at Princeton, facilitations conversation among his (very well known) colleagues –recently, for example, Molly Greene and Tony Grafton — including questions from on-campus students in the audience as well as Coursera students.

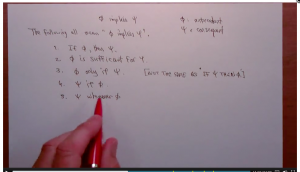

Finally, a rather unorthodox example. One of my surprise-favorite courses in this round of Coursera offerings has been “Introduction to Mathematical Thinking,” taught by Keith Devlin at Stanford. Mind, I know very little of mathematical thinking save a course in Calculus I in my first year of college … in 1998. But Devlin’s presentation is so absorbing and conversational that his pen and paper almost become interlocutors. The kinds of analysis modeled in seminar discussion are here applied to math, as he uses a verbal dialogue to lay out the steps in his thinking through each stage of a problem. It’s unexpectedly engaging.

Next time, we’ll tackle another aspect of Coursera: methods of assessment.

Leave a Response