Teaching with MOOCs: Four Cases

by Derek Bruff, CFT Director

Last month in a blog post titled “Better Than a Textbook?“, I noted that some faculty find it easier to think about the massive open online courses (MOOCs) provided by vendors like Coursera as “super-textbooks” than as actual courses. Earlier this month, Vanderbilt computer science professor Doug Fisher wrote a guest post for the blog ProfHacker titled “Warming up to MOOCs,” in which he described his experiments in using MOOCs in this fashion. Doug is teaching a graduate-level machine learning course this fall that he has “wrapped” around a Coursera course. Here’s how he describes this “wrapper” approach:

Last month in a blog post titled “Better Than a Textbook?“, I noted that some faculty find it easier to think about the massive open online courses (MOOCs) provided by vendors like Coursera as “super-textbooks” than as actual courses. Earlier this month, Vanderbilt computer science professor Doug Fisher wrote a guest post for the blog ProfHacker titled “Warming up to MOOCs,” in which he described his experiments in using MOOCs in this fashion. Doug is teaching a graduate-level machine learning course this fall that he has “wrapped” around a Coursera course. Here’s how he describes this “wrapper” approach:

With this approach, students complete the MOOC requirements of quizzes, homework and lectures, allowing both students and me to take advantage of the online discussion and grading resources. Students also have additional requirements from me, the onsite instructor of the wrapper, allowing all of us to customize and expand the course experience around a MOOC. I am running such a wrapper now as a graduate individual studies course, adding additional readings, small group discussions, and a final project to a machine learning MOOC from Stanford University.

I think this is a fascinating and potentially very effective way for faculty to make use of MOOCs. Coursera co-founder Daphne Koller seems to agree with me, having cited Doug’s experiment in her recent Forbes editorial, “How Online Courses Can Form a Basis for On-Campus Teaching.” Doug let me know about his experiment just before the fall semester began, and I’m working with Doug and a couple of graduate students to assess his use of a MOOC in this way. We probably won’t be able to determine if his “wrapper” approach is a “very effective” way of using MOOCs, but I’m pretty sure we’ll have a better sense of some of the pros and cons involved. I wonder, for instance, what value there is in interactions between a local learning community (a group of students on the same campus taking the same MOOC) and the global learning community provided by the MOOC?

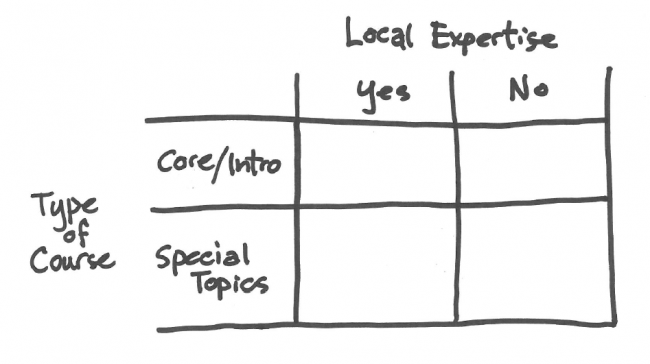

As I’ve been thinking and talking with others about Doug’s experiment, it has occurred to me that there are a couple of contextual factors that may effect the outcomes of his experiment. Doug’s course is something of a special topics course, not something taken routinely by many students. And Doug has a lot of expertise in the topic of the course, machine learning. I think it’s worth considering how his “wrapper” approach (MOOCs as super-textbooks) might play out if we vary these factors. Consider this grid:

Doug’s course falls in the bottom left square, Special Topics Courses with Local Expertise. Doug is using the online materials and interactions to change what he’s able to do during class time. Instead of introducing material through lectures, he’s leading discussions and interacting with students. In theory, this approach (similar to the “flipped classroom” model) provides a better learning experience for students.

On the bottom right we have Special Topics Courses with No Local Expertise. What kinds of courses might fall in this category? I can’t say for sure, but I imagine that the recent deal between Coursera and Antioch University might include a few such courses. Under this deal, Antioch students will be able to take Coursera courses for credit at Antioch as independent studies. My guess is that at least in some cases, students will take special topics Coursera courses that aren’t offered at Antioch. This is the kind of arrangement that Daphne Koller touted in her talk at Vanderbilt, arguing that Coursera can be used to extend the capacity of U.S. institutions of higher education–institutions that don’t have enough capacity in many areas.

It’s worth noting that, just as in a more traditional independent study, the Antioch students taking Coursera courses for credit will have local Antioch faculty as mentors. So it’s a stretch to say that there is no local expertise in the Antioch-Coursera arrangement. Perhaps it’s more accurate to say that for courses in that bottom right category, there’s not enough local expertise to run all the courses that students would like to take.

(Aside: When the Antioch-Coursera news broke, it was clear to me why Antioch students would pay tuition for these courses, since they’re receiving Antioch credit, but I wondered why Antioch would pay Coursera anything. After all, the Coursera offerings are free, right? It turns out that the Coursera terms of service prohibit students from using Coursera offerings as part of credit-bearing programs. Presumably, Antioch is paying Coursera for the right to have its students take Coursera courses for credit at Antioch.)

Back to the grid, on the top left we have Core Courses with Local Expertise. Although many of Coursera’s initial offerings were special topics courses, they’ve added a number of core or introductory courses in recent months, including Introduction to Philosophy, Microeconomics, Calculus I, and Introduction to Astronomy. These are courses taught in almost every college and university in the country, and there are plenty of faculty who have the expertise to teach these courses. Why might such a faculty member want to use Doug Fisher’s “wrapper” approach with one of these courses? Perhaps for the same reasons Doug is using the approach, to shift the content transmission portion of the course to outside of class in order to free up class time to help students assimilate and make sense of that content. (I’m using Eric Mazur’s transmission / assimilation language here.)

It’s around courses in this category that I hear the most worry from academics about labor issues. Might a university more or less outsource its introductory courses in philosophy, economics, mathematics, and astronomy to Coursera–and replace the faculty teaching those courses with adjuncts or grad students? Well, yes, but that’s already happened in many institutions. We still have tenure-line faculty teaching many core courses here at Vanderbilt, but across U.S. higher education, three-fourths of faculty appointments are off the tenure track. (As Kevin Carey notes in that commentary, the problem isn’t that adjuncts are bad teachers, it’s that adjuncts aren’t always well compensated for their work.) It’s possible that the move toward MOOCs will accelerate this process.

On the other hand, it’s also possible that MOOCs will enable tenure-line faculty to shift their time away from lecturing and toward more interactive forms of engagement with students, in both core courses and special topics courses.

The final category in the grid consists of Core Courses with No Local Expertise. When I first drew this grid, I thought to myself, What college or university would not have experts available to teach core courses? Doesn’t every institution have the capacity to offer intro to philosophy or microeconomics? Then it occurred to me that some smaller institutions or more specialized institutions might struggle to staff such courses. Might a selection of introductory MOOCs be useful to, say, an art and design institute with limited options for hiring faculty to teach liberal arts courses? I don’t know if such an institute would say to its students, “Go take this online course with no support from our faculty,” but I can see an arrangement like that at Antioch University, where local faculty are involved in helping students in some fashion, extending the capacity of more specialized institutions to offer a wider variety of courses.

There you have it: Four contexts in which MOOCs as “super-textbooks” might be useful. I see potential for educational research in each of these four contexts, since each is likely to produce at least somewhat different results for student learning. If you have an interest in research along these lines–or if you have thoughts about my set of categories here–please share in the comments.

Image: “Spices,” Nick Leonard, Flickr (CC)

Leave a Response