Ask Professor Pedagogy: A Mountain of Grading

|

Ask Professor Pedagogy is a twice monthly advice column written by Center for Teaching staff. One aspect of our mission is to cultivate dialogue about teaching and learning, so we welcome questions and concerns that arise in the classroom; particularly those from Vanderbilt faculty, students, and staff. If you have a question that you’d like Professor P to address, please send it to us. |

Dear Professor Pedagogy,

It’s fall semester, and all summer I was eager to get back into the classroom, engage in interesting discussions with my students, and see what new ideas and experiences they bring, but I’ve absolutely dreaded the mountain of grading that awaits me. This time it takes me to grade their papers and exams is ridiculous, and I end up overwhelmed as this dread overshadows anything I like about teaching. Help!

Drained by Grading

Dear Drained by Grading,

Never fear, Professor Pedagogy is here! In my younger years, I had many days of wishing I could do something to scare all of my students into dropping the course before their first major assignments were due—or at least just assign multiple-choice tests to be graded by someone else (or a machine). I suspected that I spent more time grading each paper than the student spent writing it. I became crabbier with each paper, imagining the giant stack of grading as a creature ready to gut me and steal my soul all at once. In retrospect, I’m sure these feelings came across in those copious comments in the margin: “What? You can’t be serious! This is the most ridiculous statement I’ve seen all day. Oh, except for the one in your previous paragraph.”

I then came across the notion of “Light Grading” and the advice to “Limit your comments or notations to those your students can use for further learning or improvement” on our Center for Teaching’s “Making Grading More Efficient” section of the “Grading Student Work” Teaching Guide. It made me remember something I’d heard about years before from a colleague who taught English. She talked about “Minimal Marking,” based on an article in College English in 1983. I hadn’t given it any thought since I figured it was, well, for college English classes, but according to this material and some research on student reading practices with comments on graded essays, the more “minimal” we can be in our marginal comments, the better. Let me explain.

First, what is “minimal marking”? Richard Haswell’s version applies primarily to grammar, punctuation, and other micro-level issues:

All surface mistakes in a student’s paper are left totally unmarked within the text…. Each of these mistakes is indicated only with a check in the margin by the line in which it occurs. A line with two checks by it, for instance, means the presence of two errors, no more, within the boundary of that line….. Where I feel it is useful, mistakes are explained or handbooks cited….. Until a student attempts to correct checked errors, the grade on the essay remains unrecorded.

Haswell’s specific approach saves grading time for the instructor and encourages revision and better editing from the student, but minimal marking can be extended to include larger issues of content and organization. This video effectively illustrates additional versions of minimal marking:

Before you dismiss minimal marking as just a way for overpaid, underworked professors to shirk more work, there are two pieces of information to consider. One, those markings need to be well thought-out and meaningful. More on one way to accomplish that shortly. Two, students often don’t read and/or understand feedback to their writing (Campbell, Smith, & Brooker; Connors & Lunsford; Dohrer; Gee; McCune; Norton; O’Neill & Mathison-Fife; Shepard; Straub; Treglia; Williams). The issues are complex, but to put it simply, if students don’t share your assumptions, expectations, or language about good writing, they won’t read the comments in the way they were intended. So the time you spend laboring over each essay is wasted time, hours you’ve spent instructing no one, instead of working on your research, reading a good book, running a marathon, or enjoying a good whiskey.

How do you make your minimal markings meaningful? Here’s one strategy, shared at the recent “Effective and Efficient Grading” workshop at the CFT. Determine your shorthand for the most common comments you’d make—ideally not limited to grammar and punctuation. What are the important concerns of content and organization, citation, etc., in your course? For example, if the use of illustrative examples is important, you might write “ex” in the margins. If sound logic is a significant goal, maybe “L” is a shortcut for “questionable logic.” If you emphasize a particular move or rhetorical pattern (e.g., acknowledging other perspectives, clearly asserting a position, being fair to opposing arguments), develop a shorthand for it.

Next, and most importantly, develop a legend for your codes in which you include the following:

- the shorthand code, as it’ll appear on their papers (i.e., in your handwriting if you grade by hand)

- the explanation of the code in language the students will understand, ideally language you use in the course for significant learning goals

- and where in their books, online, or elsewhere they can review the concept to fully understand it

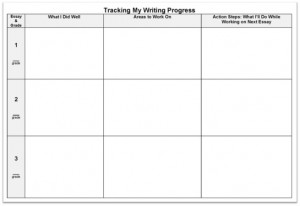

Another and even more desirable way to lessen the grading burden is to collect better and better student work. Okay, don’t knock me on the head for saying that. I know it’s obvious and of course what we want, but how do we get there? Let’s see if this additional step helps. Make sure you’re not the only one tracking the students’ progress throughout the semester; require them to do so as well. I don’t mean you should simply have them keep track of their grades. Instead, I mean something more intensive, something that guarantees they’ll read your comments and develop appropriate strategies for improvement. (Of course, they then have to implement those strategies, but if they write them down, they’re more likely to stick to it.) So as you develop a way of tracking their progress from paper to paper or exam to exam (strengths, weaknesses or “areas for improvement,” and strategies for improvement), require students to do the same.

Such a document can be helpful to you and to the students. You can keep it handy while grading, noticing any patterns of improvement or the lack thereof. Students can keep it handy while drafting or studying, using it to build on their strengths, focus on their weaknesses, and apply their strategies for success. Notice how this simple technique facilitates students’ metacognitive checking-in on their writing or studying processes. Such self-assessment—here guided by your feedback but translated into their own explanations and strategies—helps students develop a habit of regulating their own learning (Boud and Falchikov; Shepard; Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick).

So cheer up, Drained by Grading. Soon, you’ll be grading with a swift pen and spending more time on other things. I vote for the whiskey.

Professor P.

References

- Boud, David and Nancy Falchikov. “Aligning Assessment with Long-Term Learning.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 31.4 (2006): 399-413.

- Campbell, J., D. Smith, and R. Brooker. “From Conception to Performance: How Undergraduate Students Conceptualise and Construct Essays.” Higher Education 36 (1998): 449-469.

- Connors, R.J. and Lunsford, A.A. Teachers’ rhetorical comments on student papers. College Composition and Communication 44 (1993): 200-223.

- Dohrer, Gary. “Do Teachers’ Comments on Students’ Papers Help?” College Teaching 39.2 (1991): 48-54. EBSCOhost. Web. 7 Nov. 2011.

- Haswell, Richard H. “Minimal Marking.” College English 45.6 (1983): 166-70.

- Gee, Thomas. “Students’ Responses to Teacher Comments.” Research in the Teaching of English 6 (1972): 212-21. JSTOR. Web.

- McCune, Velda. “Development of First-Year Students’ Conceptions of Essay Writing.” Higher Education 47.3 (April 2004): 257-282.

- Nicol, David J., and Debra Macfarlane-Dick. “Formative Assessment and Self-Regulated Learning: A Model and Seven Principles of Good Feedback Practice.” Studies in Higher Education 31.2 (2006): 199-218.

- Norton, L.S. “Essay Writing: What Really Counts?” Higher Education 19 (1990): 125-138.

- O’Neill, P., and Mathison-Fife, J. “Listening to students: Contextualizing response to student writing.” Composition Studies 27(1999): 39-51.

- Shepard, Lorrie A. “The Role of Assessment in a Learning Culture.” Educational Researchers 29.7 (Oct 2000): 4-14.

- Straub, Richard. “Students’ Reactions to Teacher Comments: An Exploratory Study.” Research in the Teaching of English 31.1 (1997): 91-119. JSTOR. Web. 25 Aug. 2011

- Treglia, Maria O. “Feedback on Feedback: Exploring Student Responses to Teachers’ Written Commentary.” Journal of Basic Writing 27 (2008): 105-37.

- —. “Teacher-Written Commentary in College Writing Composition: How Does It Impact Student Revision?” Composition Studies 37 (2009): 67-86.

- Williams, Sue Ellen. “Teachers’ Written Comments and Students’ Responses: A Socially Constructed Interaction.” Conference on College Composition and Communication. Phoenix, AZ: ERIC Document Reproduction Service, 1997. Web. 7 Nov. 2011.

Leave a Response