Building an effective teaching assistant orientation using a data-informed backward design approach

- Teaching Assistant Orientation at Vanderbilt University

- Understanding by Design

- Identify Desired Results

- Determine Acceptable Evidence

- Gather Pre-Instruction Evidence

- Plan Learning Experiences and Instruction

- Gather Post-Instruction Evidence

- Conclusion

Teaching Assistant Orientation at Vanderbilt University

Each year the Vanderbilt Center for Teaching (CFT) holds an orientation event for graduate students beginning work as teaching assistants: Teaching Assistant Orientation (TAO). This event happens the week before classes begin and covers common duties (grading, office hours), policies/regulations/resources (FERPA, honor code), technology (course management software), and guidelines for creating a safe and inclusive classroom.

TAO is led by CFT graduate student workers, called Teaching Affiliates (TAffs) who are largely responsible for the structure and implementation of their individual TAO session. I led three TAO sessions in the summers of 2018-2020 for students in various engineering departments.

Traditionally, TAO is an in-person, day-long event held one week before classes begin. The sessions are generally a mixture of lecture (often supplemented with multimedia such as videos), group discussion, and hands-on activities that include extensive participant interaction and collaboration. One example may be practice leading a recitation by having participants break into small groups and deliver one-minute-lectures on any topic they choose to then receive feedback from their peers.

The COVID19 pandemic required universities to move instruction online beginning in the Spring of 2020. This made an in-person TAO 2020 event impossible. Instead, TAO was converted to a fully online format where, instead of meeting for one full day, TAO became a three-day event conducted via Zoom and Brightspace. Students would dedicate 3 hours per day to TAO: two face-to-face hours in the morning and one asynchronous hour of work to complete online modules. One hour of face-to-face time would be dedicated for an experienced TA panel discussion. This new structure presented a unique challenge to build an effective TAO session.

The purpose of this post is to analyze the session design strategy I used to build my TAO session in these unique circumstances. This analysis may prove useful for those seeking to build similar online workshop-type events.

Understanding by Design

Backward Design, an instructional framework detailed in the book Understanding by Design by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe, is one of the methodological cornerstones that guides CFT practice.

Forward Design, the framework more commonly encountered in an academic career, is characterized by course goals arising secondary to course content and activities. Designing a class that simply follows each chapter of a textbook and assigning course goals based on this content is an example of Forward Design.

Backward Design, in contrast, involves initially defining course goals and then choosing teaching activities to achieve these goals. These course goals can be based on the instructor’s expertise, national standards, or necessary career skills (and is often a combination of factors). Following the previous example (following each chapter of a textbook then designating course goals), an instructor using Backward Design may elect to use useful passages, activities, or assessments from the textbook while also utilizing other resources (primary sources, guest lectures, relevant films, etc.) to develop a more comprehensive course in order to achieve the initially defined course goals.

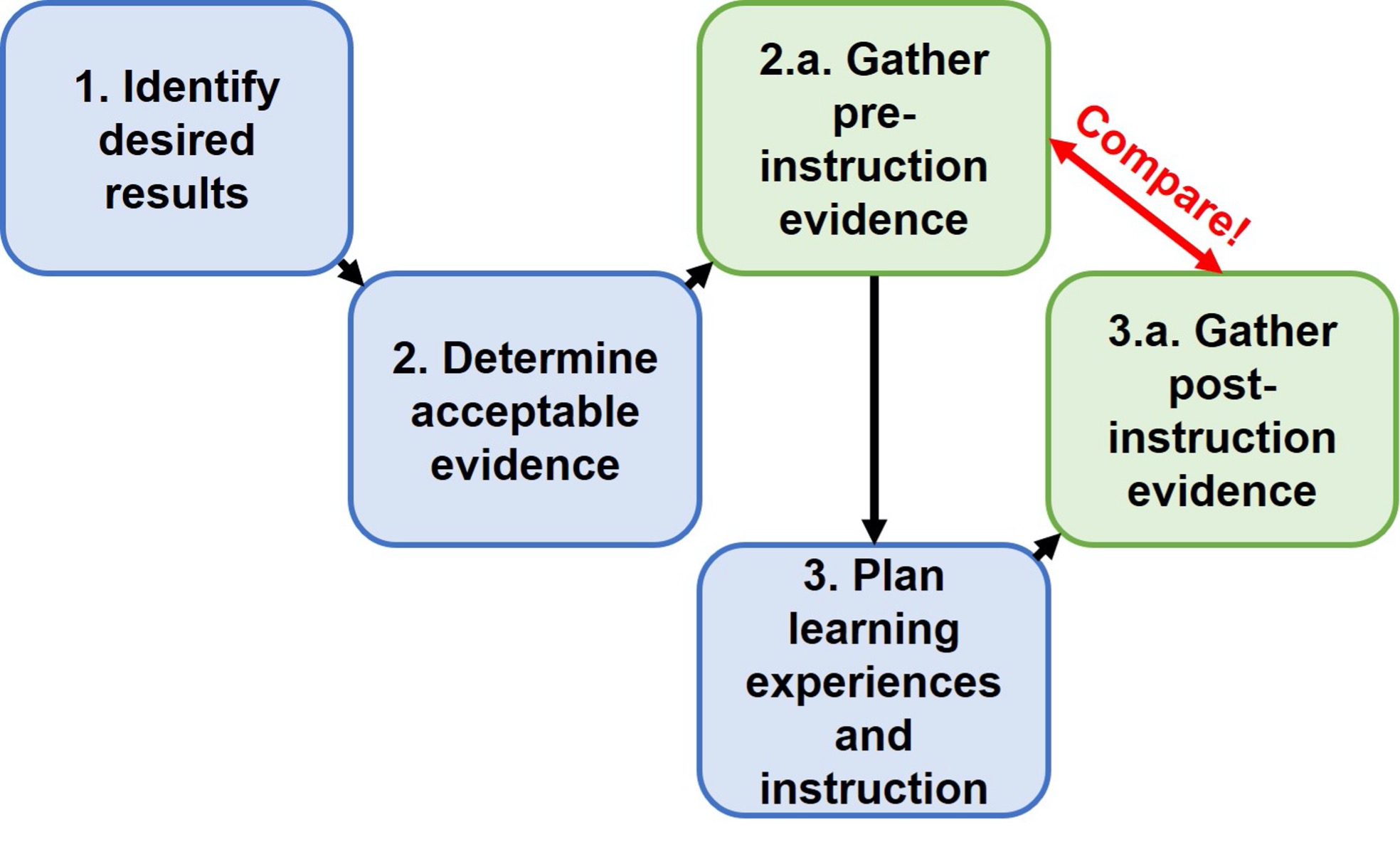

The basic Backward Design process is a three-step framework: 1. identify desired results, 2. determine acceptable evidence, 3. and plan learning experiences and instruction.

Backward Design begins with the final course goals in mind. What are the desired outcomes of the students in the class? What new knowledge and skills should result from completing the course? Of these, which are the most crucial and which are secondary? This mindset allows for selection of high-impact activities to meet highly prioritized course goals. Designing with end-goals in mind ensures that course content is chosen with intention in order to achieve a system-level understanding of the course topic.

After the goals of the course are defined, the method of assessing student learning is developed. Assessment can take many forms such as quizzes, tests, group projects, surveys, and informal methods such as in-class discussion, online discussion boards and blog posts, etc.

Only after these steps are the individual content and activities chosen. Being mindful of goals and assessment results in an intentional course structuring always with the end goals directly informing the choice of each activity, reading, discussion topic, and more.

I used this framework to develop my virtual TAO 2020 course. I also made slight adjustments to the Backward Design process in order to systematically assess the success of my TAO session. Using short surveys, I asked participants to self-assess their attitude and content knowledge with regard to their upcoming TA duties. The survey was sent before and after TAO in order to track changes in student attitude and content knowledge. With this in mind, I used the following custom Backward Design framework to structure my TAO session:

Figure 1. Modified Backward Design Schema. The course design framework defined in Understanding by Design was slightly modified to include real-time data integration and analysis.

Figure 1. Modified Backward Design Schema. The course design framework defined in Understanding by Design was slightly modified to include real-time data integration and analysis.

Using this strategy allows me to structure the session in a way that ensures areas of greatest need are adequately covered and if participant attitudes toward becoming TA improve. The relative success of my session can be determined by tracking the survey responses and seeing if there are improvements after the TAO session.

Identify Desired Results

The content of TAO is defined by the CFT and the discretion of the TAffs. TAffs are expected to know the common roles and duties of TAs in their departments and tailor the individual session to meet these needs. Broadly, the goals of TAO are the improvement of student attitudes and content comfort and knowledge.

After TAO participants should feel: LESS scared, LESS nervous, MORE prepared, and MORE excited about becoming a TA.

Students should IMPROVE their comfort/knowledge in:

Common TA Duties

- Lead lectures/recitation

- Leading a lab

- Grading

- Holding Office Hours

Common Policies, Resources, and Regulations

- Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA)

- Student accommodation services

- The Honor Code

- Being a Mandated Reporter of Abuse

Creating a Welcoming Learning Environment

- Creating a Safe and Inclusive Classroom

- Helping Students in Distress

Educational Technology

- Course Management Software (Brightspace)

- Video Conferencing Software (Zoom)

Determine Acceptable Evidence

Evidence of course goal achievement is often based on formal assessment of knowledge and skills using tests, quizzes, labs, or projects. Informal assessment can also occur by interpretation of class discussions or feedback surveys. The time constraints of the TAO session make extensive formal assessment difficult. While some knowledge should be internalized by the participants, the broader goal of TAO is to give TAs tools, resources, and some practice in essential TA skills. This means participants will likely not become content experts but will instead become more comfortable operating as a TA. With this in mind, assessment was performed using pre- and post-TAO surveys which queried TAs on their outlook on becoming a TA and their confidence and knowledge in various important domains.

I defined a successful TAO session as having a statistically significant change between pre/post-TAO responses (based on desired results defined in section II. a.) The paired Student’s t-test was used for the comparison and only participants who completed both surveys would be used. Students were given three days to complete the pre-TAO survey (August 14th to 16th) and three days to complete the post-TAO survey (August 19th to 21st).

Gather Pre-Instruction Evidence

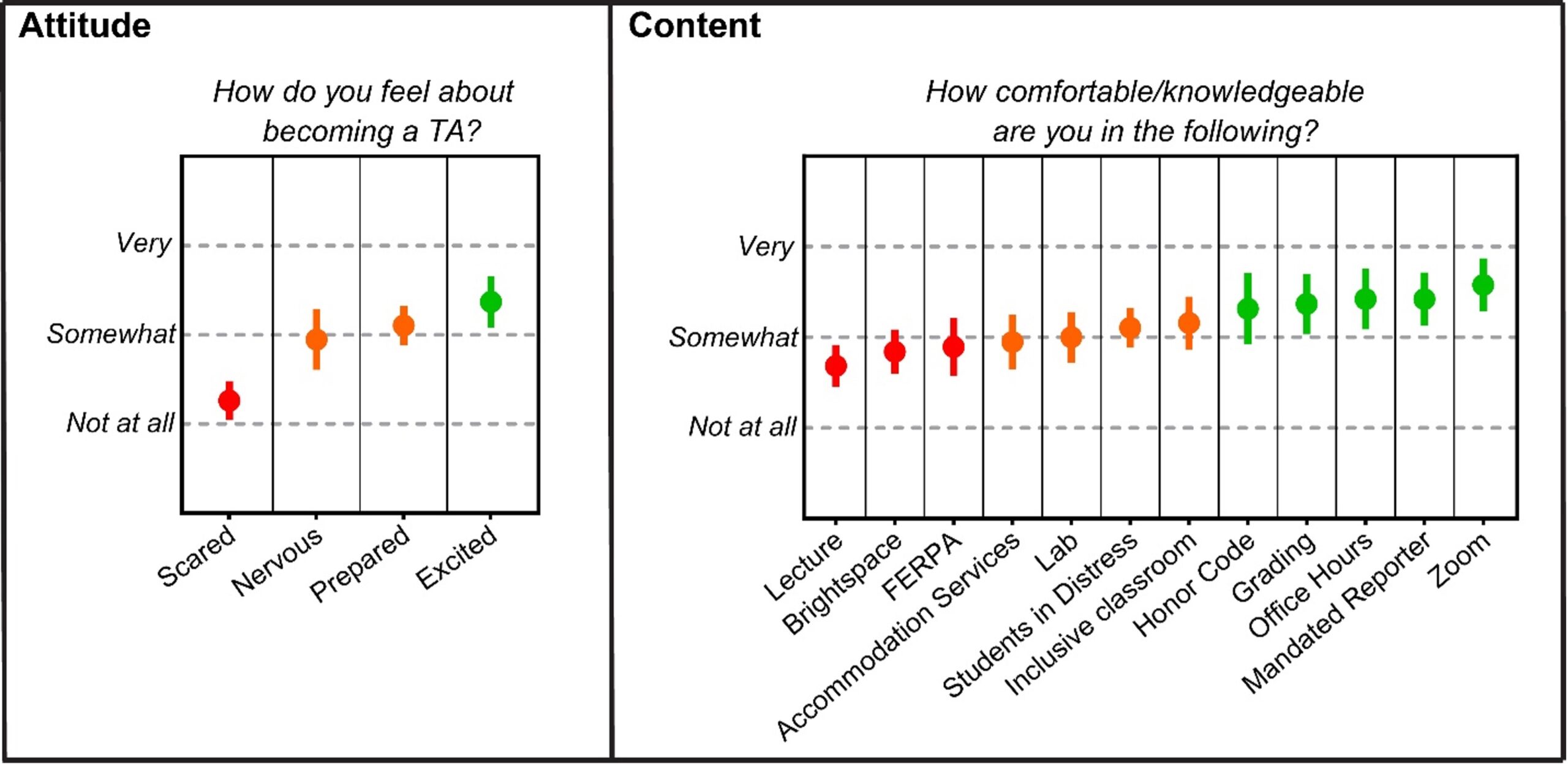

19 of 25 (76%) participants’ survey responses were analyzed. The survey used 3-point Likert-like design and answers were converted to numerical values for statistical analysis: ‘very’ (indicating strong agreement) converted to ‘3’, somewhat (moderate agreement) to ‘2’, and not at all (disagreement) to ‘1’. The paired student’s t-test was run on the converted values.

Results are displayed as mean and 95% confidence interval and ordered from lowest to highest. Results were roughly color-coded as red, orange, and green from indicating lower to higher agreement.

Figure 2. Pre-TAO Survey Results. Survey responses prior to TAO were ordered and color-coded from lowest to highest agreement.

Figure 2. Pre-TAO Survey Results. Survey responses prior to TAO were ordered and color-coded from lowest to highest agreement.

Students rated themselves as very excited, moderately prepared, moderately nervous, and not at all scared to become a TA. There was considerable variability in content areas where students felt most and least comfortable. Students felt unprepared for TA duties such as leading a lecture or educational technology topics like using Brightspace. In contrast, participants were quite confident in technology such as Zoom, policies like the Honor Code, and skills such as grading. Most topics fell somewhere in the middle.

I could now use this baseline data in tandem with CFT guidelines and my personal experience to plan the structure of my TAO session.

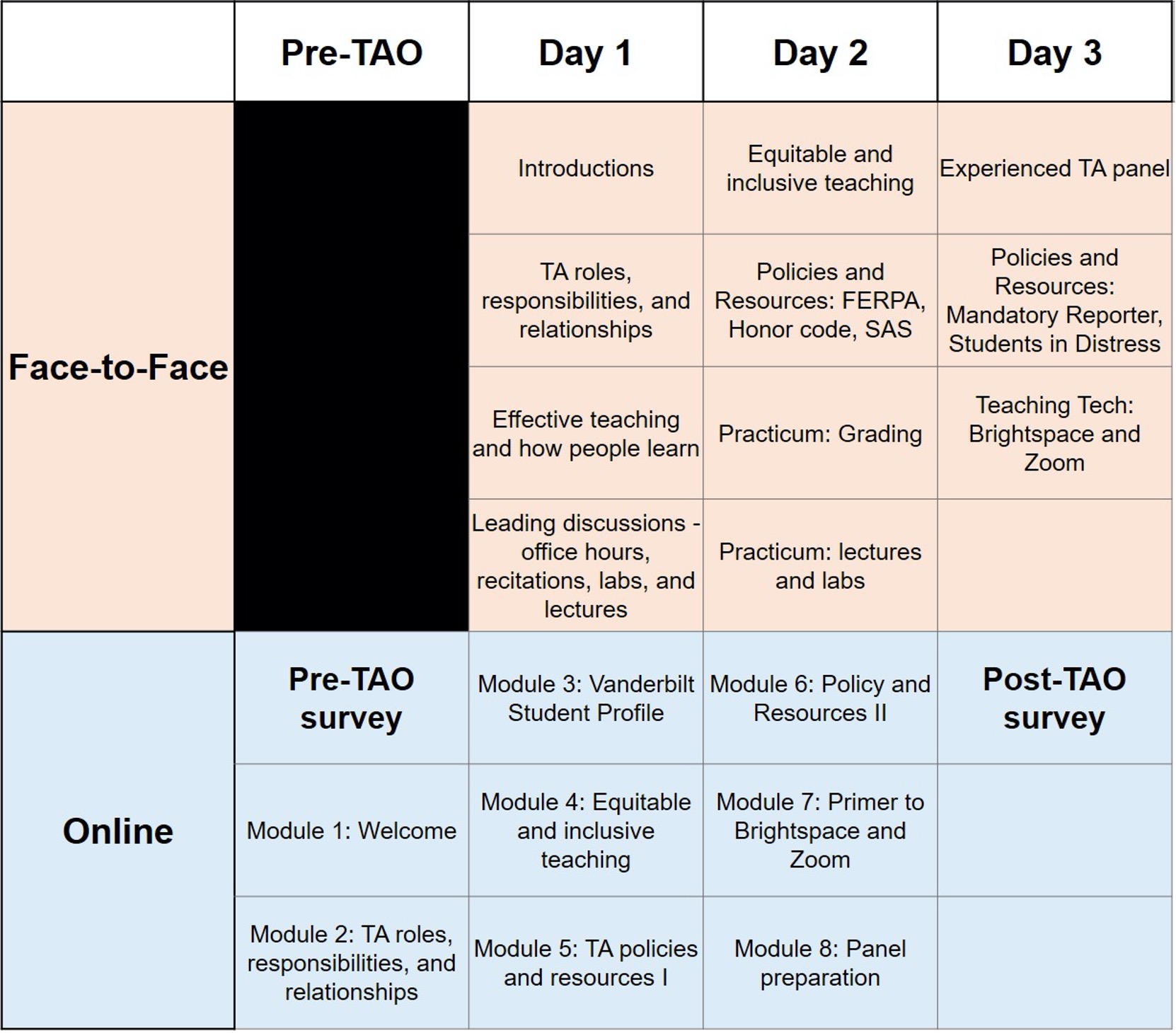

Plan Learning Experiences and Instruction

The challenge of building an online TAO session is making sure the 5 hours of face-to-face time are spent on the areas of highest need. Less crucial or content students are already confident in can be completed in the 3 hours for online modules or provided as supplementary materials.

Leading lectures (in classes, office hours, and recitations) and labs are common duties of TAs in the Biomedical and Chemical Engineering departments. They were also topics that students indicated lower confidence in the pre-TAO survey. As a result, these topics were considered high priority and a large amount of face-to-face time was dedicated to them. For example, useful discussion frameworks such as the INSPIRE guidelines were introduce and the participants were then able to practice the concepts with their peers in small breakout sessions by conducting short practice lectures and receiving feedback.

Policies such as FERPA and campus resources like Student Accommodation Services are crucial knowledge for new TAs and the pre-TAO survey indicated low knowledge in these topics. Online and face-to-face content was used to address these areas. Students first watched videos, read web resources, and discussed their questions on a discussion board in Brightspace. This helped students get acquainted with the material and identify areas of uncertainty. The following day we used face-to-face time to discuss the policies, address lingering questions, and work in small groups to address common case studies.

Vanderbilt and the CFT strive to create an inclusive environment in the classroom. The pre-TAO survey indicated a moderate amount of prior comfort in inclusive teaching topics so instruction was split between online and face-to-face. Students first completed an online activity – the Alex activity, developed by fellow TAff Cait Kirby – to help uncover and understand implicit biases. Participants discussed the activity in a message board and then watched videos on subjects like stereotype threat and implicit biases. The following day we discussed the Alex activity during face-to-face time and addressed related case studies in small groups. A think-group-share strategy was used to let students consider the cases, discuss with their peers, then bring their thoughts to the larger group for discussion.

I was also able to budget my limited time by moving lower emphasis content to online modules and optional supplements. For instance, students were already highly proficient using Zoom so I did not include any face-to-face time on this material. University resources for technical assistance were provided as optional materials and I offered to meet individually if participants did need help with Zoom.

Students indicated prior confidence in topics like office hours and grading but these are very important duties of TAs in Biomedical and Chemical Engineering so I elected to combine the topics with similar material or to include face-to-face instruction anyways.

One interesting challenge was Vanderbilt’s course management software, Brightspace. Participants indicated this as an area of low prior knowledge. While navigating Brightspace is important for TAs, TAO is not meant to focus on learning management software but instead important laws, policies, regulations, and effective pedagogies. In previous years I had simply referred students to the Vanderbilt Brightspace office or provided short tutorials on the most common functions such as entering grades. I was able to leverage the online TAO structure to meet this challenge. Optional Brightspace tutorials were completed during asynchronous time with sandbox courses created for each participant. Students could use the sandbox course to experiment with various Brightspace functionalities without having to use a live course. A small amount of face-to-face time was set aside for addressing specific Brightspace questions submitted by the participants.

These are some of the examples which illustrate the utility of combining pre-TAO survey data with CFT guidance to structure a TAO session that prioritized high impact concepts and maximized the time available to best train students. A summary of my TAO session structure is presented below:

Table 1. TAO Session Structure. A general summary of the final structure of my TAO 2020 section separated into online modules and face-to-face activities.

Table 1. TAO Session Structure. A general summary of the final structure of my TAO 2020 section separated into online modules and face-to-face activities.

This efficient time allocation meant adequate time was spent in the most important areas all while never going over time or skipping any material.

Gather Post-Instruction Evidence

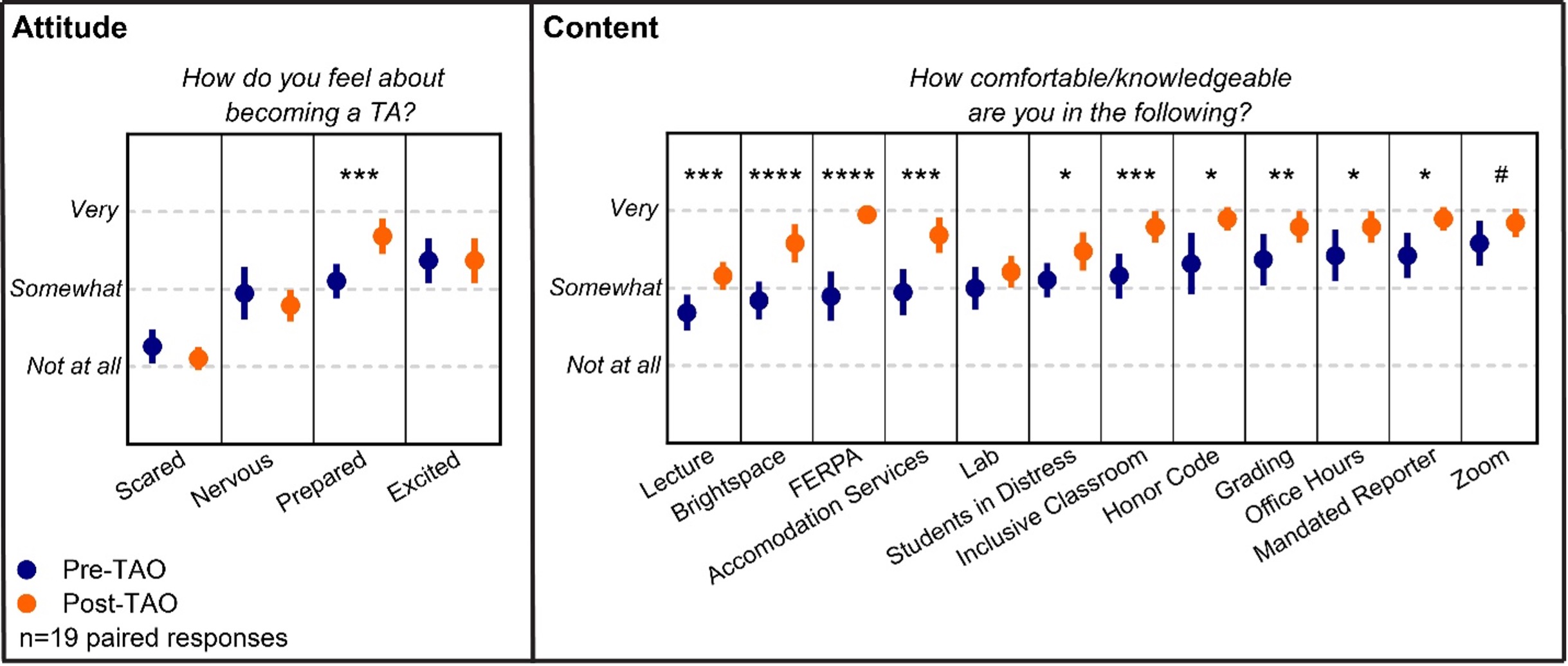

The post-TAO survey was released after the last face-to-face session. This survey was identical in format to the pre-TAO survey. The paired Student’s t-test was used to determine if there was a significant change in student response between pre- and post-TAO surveys. Data is displayed as mean and 95% confidence interval. Pre-TAO is designated in navy while post-TAO are orange. P-values are indicated as follows: # p<0.1, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001. The topics are in order from lowest to higher pre-TAO response mean (left to right).

Figure 3. . After completing TAO, the survey was collected again to compare how attitudes had changed after the session. Data is presented as mean +/- 95% confidence interval. Pre-TAO in navy and post-TAO in orange. Paired student’s t-test was performed for each topic. : # p<0.1, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001.

Figure 3. . After completing TAO, the survey was collected again to compare how attitudes had changed after the session. Data is presented as mean +/- 95% confidence interval. Pre-TAO in navy and post-TAO in orange. Paired student’s t-test was performed for each topic. : # p<0.1, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001.

Students felt significantly more prepared after completing TAO but feelings of excitedness, nervousness, or scaredness did not change (the latter two trended downward but were not statistically significant, p=0.18). These results indicate that the TAO session improved the most crucial attitude for participants – feeling more prepared. While many students did report feeling less scared, less nervous, and more excited, it was more common that students reported no change in these attitudes.

There were marked improvements in knowledge and comfort in most topics covered in the TAO session. There were striking improvements in both low (lecture, Brightspace, FERPA, and Student Accommodation Services) and high (grading, office hours) confidence content areas as determined by the pre-TAO survey.

Relative changes were greatest in topics related to technology, policy, resources, and regulations. Less tangible TA skills like leading a lecture or lab show modest or no improvements, respectively. These are complicated topics that are difficult to provide training in during abbreviated online sessions. Emphasis should be placed on providing students opportunities for practice and resources in these domains, if possible.

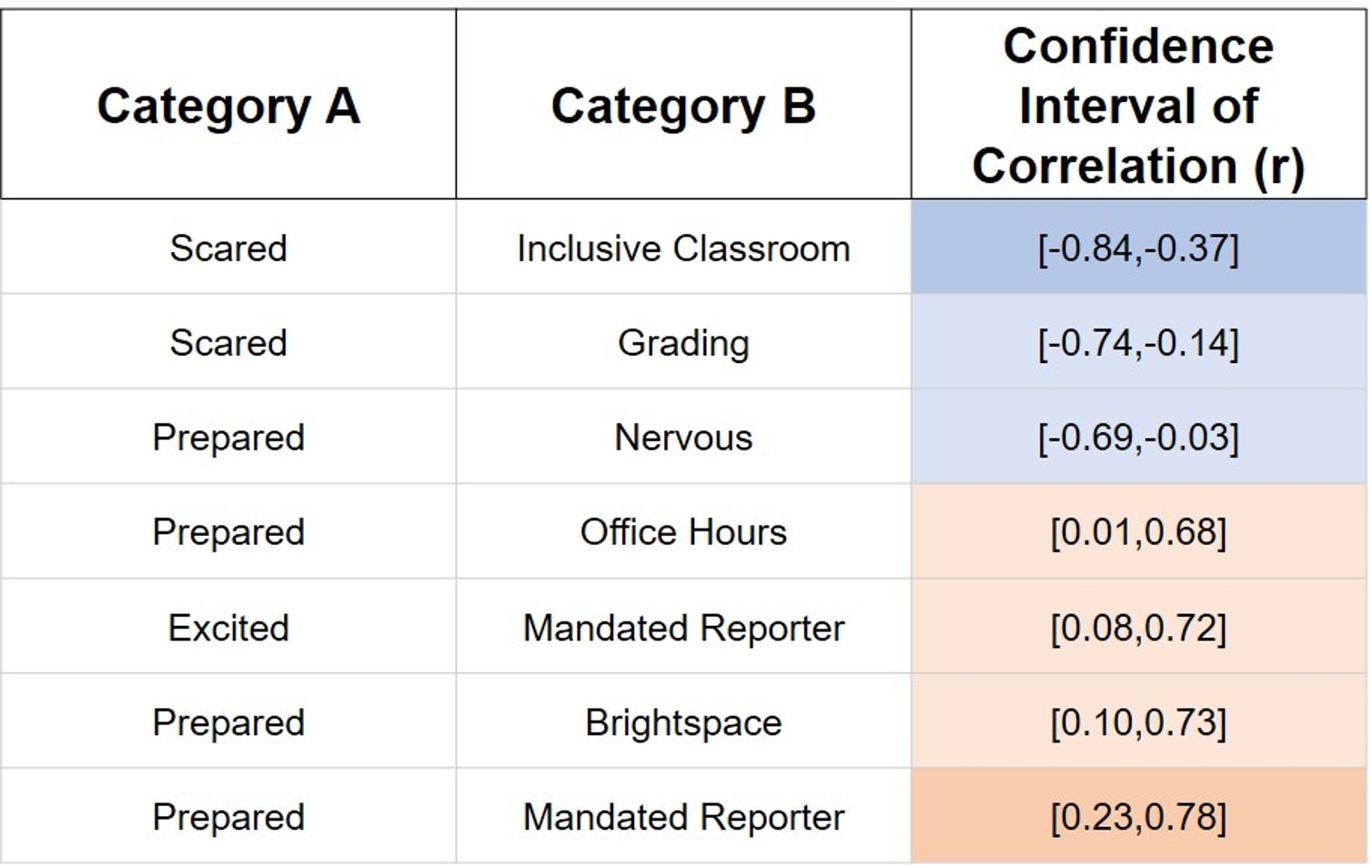

Finally, correlation analysis was used to see if any interesting relationships occurred between attitude and content knowledge changes. The survey response change was recorded as an absolute change by subtracting the numerical value of the post-TAO response from the pre-TAO response. For instance, a student marking ‘somewhat’ confident in a topic pre-TAO then marking ‘very’ confident in the same topic post-TAO would be assigned +1 in this domain. A correlation matrix was produced to analyze the relationship between changes in each survey topic. Correlations where the 90% confidence interval of the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) did not intersect with zero (no correlation) were reported in Table 2. Positive correlations were filled with shades of orange while negative correlations where shaded in blue. Pearson correlation coefficients closer to +/- 1 indicate a stronger relation between the factors.

Table 2. Significant correlations. The Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) was computed on the absolute change pre/post-TAO for each topic surveyed. Significant correlations (p<0.1) were noted and the 90% confidence interval of the mean is displayed in the right column.

Table 2. Significant correlations. The Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) was computed on the absolute change pre/post-TAO for each topic surveyed. Significant correlations (p<0.1) were noted and the 90% confidence interval of the mean is displayed in the right column.

A number of interesting relations arose from this analysis. There was a negative correlation between feelings of nervousness and preparedness mean students felt more prepared after TAO tended to also feel less nervous. Improved content knowledge in Office Hours, Brightspace, and being a Mandated Reporter most often tracked with feelings of being more prepared. The strongest variable relation was the negative correlation between feelings of scaredness and knowledge of creating an inclusive classroom meaning students that felt more confident in this content after TAO also tended to feel less scared. One of the primary goals of TAO is to empower TAs to create a learning experience that is free of racism, sexism, classism, and all other forms of discrimination and it is pleasing learning about these topics helped students feel less scared to TA. While these are only correlations and not causative roots of attitude changes, they are interesting relationships which back up the approach of TAO formulated by the CFT.

Conclusion

TAO is a CFT event which trains incoming TAs on topics related to their new role. Traditionally an in-person workshop-style event, the COVID-19 pandemic caused TAO 2020 to transition to an online format. This presented an interesting teaching challenge which was amenable to a Backward Design approach. Combining this framework with real-time data analysis to fine tune the course structure produced a session which focused on high impact material, efficient usage of face-to-face instruction, and systematic analysis of student attitudes and content knowledge before and after completing the workshop.

Results indicate that this strategy was very effective in improving participant preparedness. Surveys also indicated increased student knowledge nearly all relevant content areas. The most striking improvements were in topics like FERPA, Brightspace, Accommodation Services, and creating an inclusive classroom. There were modest or no improvements in leading labs and lectures. These broad skills are difficult to teach thoroughly in a short, online workshop but an effort should be made to give students the practice and resources the need to become more confident in these topics.

Correlation analysis showed a number of interesting relationships. Students who noted increased feelings of preparedness also tended to feel less nervous. Increased content knowledge in topics like office hours, Brightspace, and mandated reporting significantly correlated with feeling more prepared. While all of the TAO content topics are important, it is important to note that these specific areas correlated very strongly with feelings of increased preparedness.

Improvements in knowledge of topics related to creating an inclusive classroom (avoiding and confronting bias and discrimination) strongly correlated with feeling less scared about becoming a TA. These topics are often a major point of anxiety and contain some challenges that are difficult to discuss. However, creating a welcoming environment for all students regardless of gender identity, race, religion, class background, etc. is an imperative goal of Vanderbilt and the CFT. These data back up the focus on these challenging. Becoming well-versed in these topics is imperative for a good TA and this evidence shows that working through these topics at TAO can make the new role feel less daunting.

Using a data-driven Backward Design approach is an effective method for intentionally structuring and evaluating the efficacy of an online, workshop-style course such as TAO 2020. This specific case study provides general support for further application of the approach by instructors looking to create similarly effective online training classes.

.

.

.

.

.