Steps to creating more valid (and less stressful) exams

Test blueprints Partial credit Sequencing Question writing

Use test blueprints

The first and perhaps most important recommendation for constructing exams is to consider what should be on it before you start writing. What content should the exam cover? What skills should students demonstrate? What fraction of your test should require higher order thinking, and what fraction should measure basic knowledge?

To clarify the answers to these questions, it is good practice to construct a table of specifications (aka, a test blueprint) to guide your test writing (Brame, 2019; see chapter 12). A test blueprint characterizes the distribution of points across content areas and types of thinking you want the test to target.

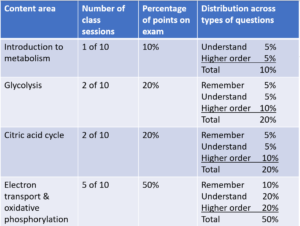

It can be easiest to start with a distribution of points across content areas. The table shows one way to do that, with the number of points corresponding to the amount of time spent in class.  The test blueprint can then expanded to include the types of thinking you want the students to do within each content area. Then, as you think about questions, it’s helpful to consider your learning objectives for each content area (example learning objectives for the content areas in the table can be seen here).

The test blueprint can then expanded to include the types of thinking you want the students to do within each content area. Then, as you think about questions, it’s helpful to consider your learning objectives for each content area (example learning objectives for the content areas in the table can be seen here).

The biggest benefit of a test blueprint is that it can help you stay on track as you write the test, making sure that you test the content and ways of thinking that matter to you. It can also be a good way to communicate with your students. Sharing the test blueprint–or an abbreviated form of it–with them can help them prepare and reduce their uncertainty about what to expect.

Include opportunities for partial credit that are efficient to grade

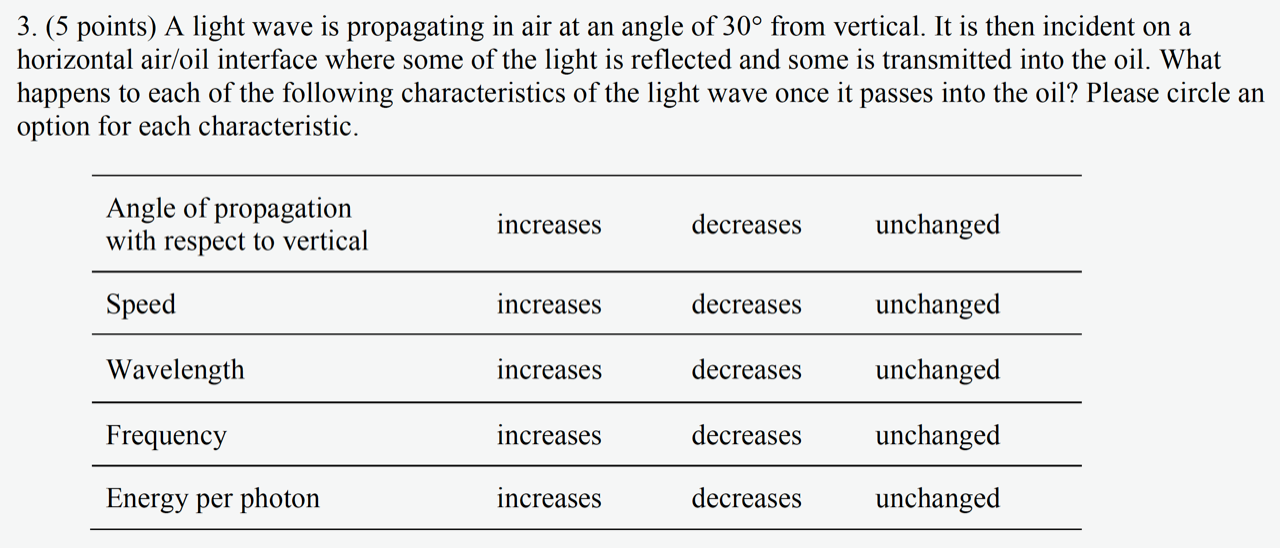

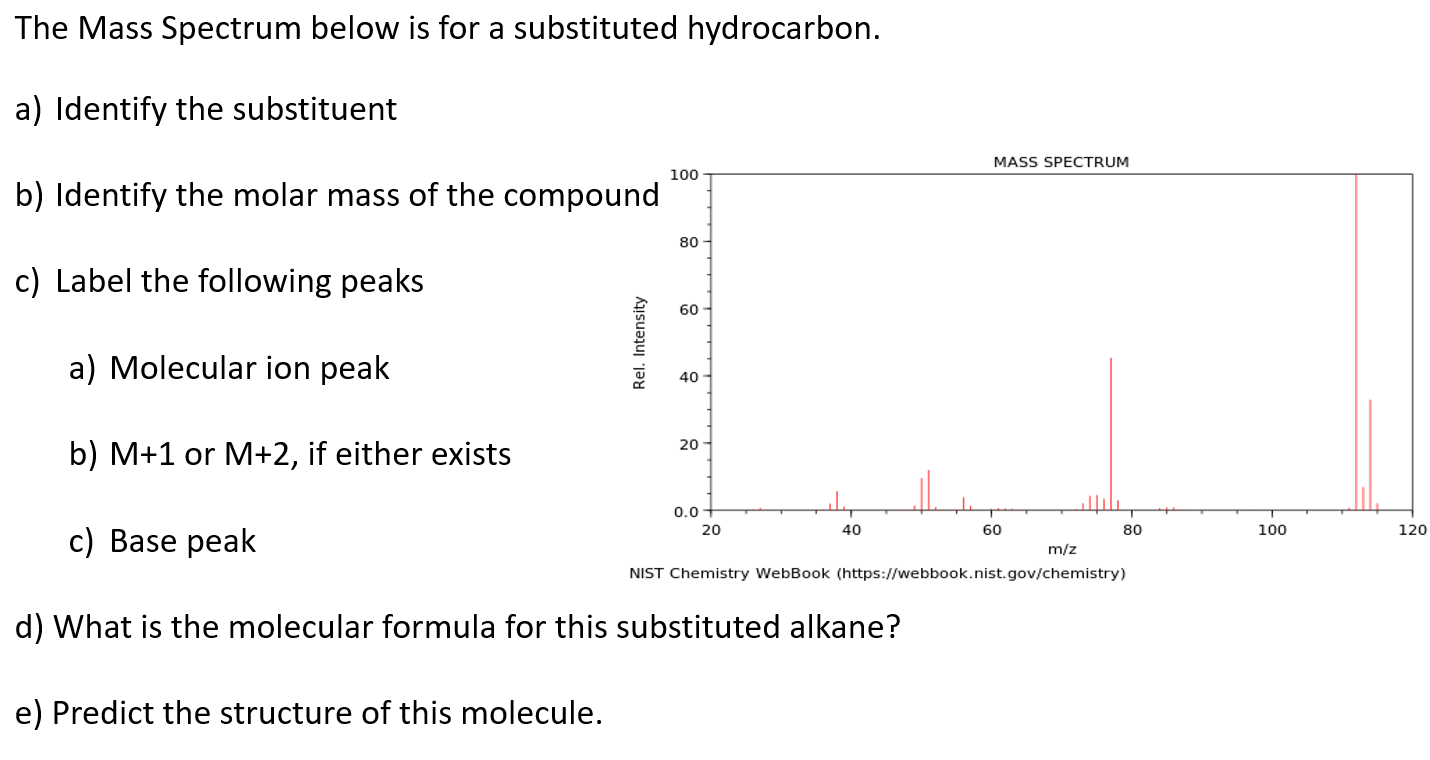

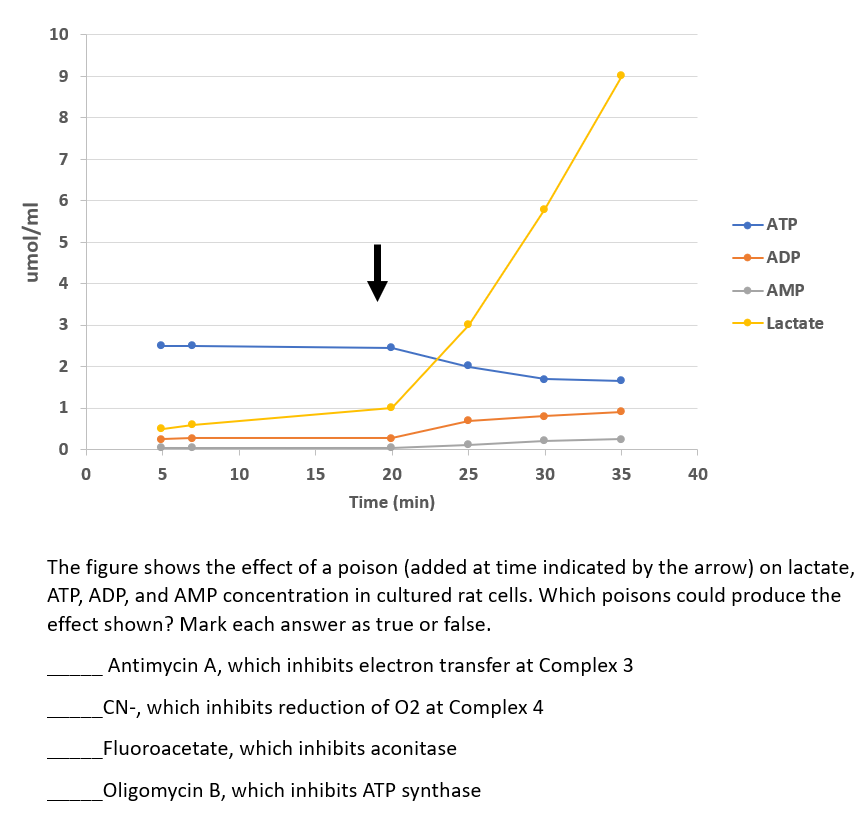

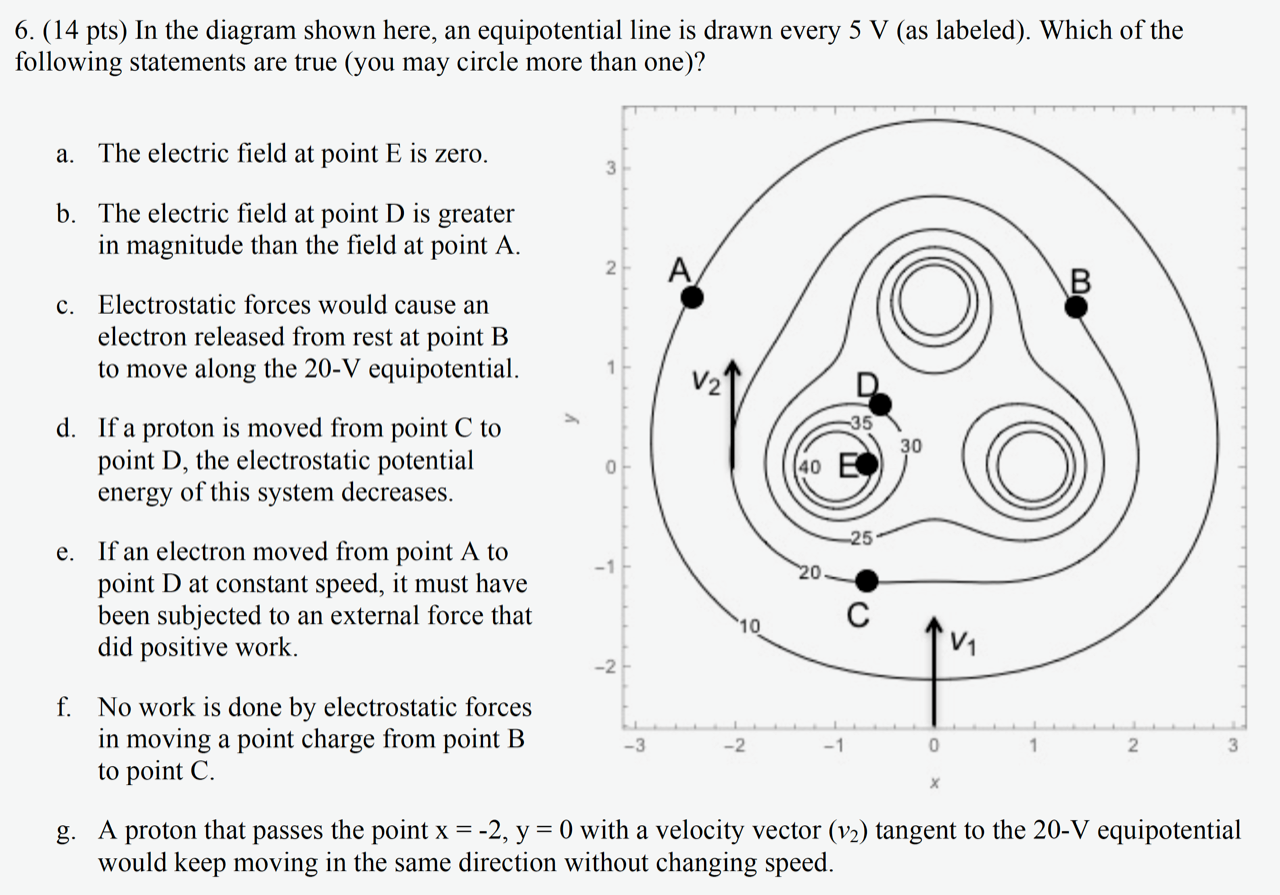

Question clusters. In a question cluster, students are given an initial prompt, such as a graph or a scenario, and are then asked multiple short questions about the prompt. These questions can be MC or short answer; the key is that each has an answer that students can provide independently of other questions and that you can grade efficiently. Two examples are given below.

When creating question clusters, it’s important that mistakes students make on the first or second question don’t result in all incorrect answers on later questions. Ideally, the questions in a cluster should be independent of each other; if that’s not possible, it’s wise to grade the later questions based on the first false assumption (while clearly identifying to students the problematic thinking on the earlier question).

Multiple true/false.

Another way to create opportunities for partial credit is to use “choose all correct” questions, which might more accurately be regarded as multiple true/false items. That is, the student can evaluate each response as a true or false response to the stem, and you can grade it as such. Thus a student could get from 0-5 points for a question with 5 alternatives. These items have additional benefits: they are often easier for the instructor to write, and Brian Couch and colleagues have also shown that they more effectively reveal partial understanding. Two examples are shown, one from a biochemistry course and one from a physics course.

Multiple choice questions with more and less correct distractors. Some faculty provide opportunities for partial credit in multiple choice questions by offering distractors (or incorrect answers) that are more and less correct. For example, if the one best answer for a MC question is a particular dehydrogenase, then a distractor that named another dehydrogenase might be worth partial credit, whereas a distractor that named a different type of enzyme might be worth no credit. In another example, if the question required computation, then a distractor that changed the sign might be worth partial credit, whereas a distractor that had the wrong digit might be worth no credit.

.

Sequence questions intentionally

Exam questions can be sequenced in the order in which topics were discussed in class, by difficulty, or randomly. While a recent review of the literature on psychology exams indicated that ordering did not impact overall student performance, it did find that some studies reported cognitive and/or affective benefits of intentional question sequencing (Hauck et al., 2017). Specifically, ordering questions by lecture sequence can improve student performance, and sequencing questions from easier to harder can improve student confidence during and after test-taking (Weinstein and Roediger, 2010; Jackson and Greene, 2014). To improve student experience during test-taking, it therefore makes sense to choose an intentional order to present exam questions.

Use good practice in question writing

Of course, aligning the exam with what you have taught and intend to assess is only half the battle; the other half is writing questions that are valid measures of your students’ knowledge. If you use multiple choice questions, the key is to write questions that 1) don’t give unintentional clues to the correct answer, and 2) that assess the desired skill and knowledge and not something else, such as working memory or non-target vocabulary. This guide provides detailed guidance, but in essence, you can follow these rules :

The stem (that is, the question or prompt) should

- Be meaningful by itself and present a definite problem

- Contain only relevant material

- Avoid negative construction (i.e., “which of the following is not…” or “all of the following except…”

The alternatives should

- Be plausible

- Be stated clearly and concisely

- Not include “all of the above” and “none of the above”

- Be presented in a logical order (e.g., alphabetical or numerical)

- Be free from clues about which response is correct, such as difference in length (we write longer correct answers than distractors!) and use of absolutes (it’s really hard to get a scientist to say “always”).

It’s important to avoid complex multiple choice (e.g., A only; A and B; A and C; A, B, and C). “Choose all correct” questions that essentially function as multiple true/false can have the same benefits without the excessive demand on working memory. It’s also important to know that the number of alternatives can vary among items; there is little difference in difficulty, discrimination, or reliability among items with three, four, or five alternatives.

For free response questions, Hogan and Murphy provide a few recommendations to maximize the effectiveness of constructed response items (Hogan and Murphy, 2007).

- Be transparent about the point values of the item or the time students should allot to answering the question. This can be written on the test next to the item.

-

Example. Free response question from a genetics course. Courtesy of Kathy Friedman. Define the question or task clearly, using verbs that ensure students know what they’re supposed to do. For example, the verbs compare, sketch, and predict point to clear actions that students should take in constructing their answer. It can be particularly important for questions that ask why an event or phenomenon occurs; students may be unclear about whether to explain the mechanism or the purpose. The question at right has a final sentence, in italics, that emphasizes the elements students should include in their answer.

- Have a colleague or teaching assistant review free response questions.

- Develop a rubric or other scoring strategy, such as a checklist, when you write the item. This helps ensure that the question is testing the skills and knowledge that you intend, and it helps ensure consistent grading, which is one of greatest challenges for free response questions.

Other sections:

- The perils of curving: Centering the grade average

- Class structures that minimize anxiety about exams

<<Back to the beginning

.

.

.

.

.

.