SoTL Spotlight: Bringing a Scholarly Approach to Vanderbilt’s Classrooms

by Nancy Chick, CFT Assistant Director

Nancy is the author of a variety of SoTL articles and book chapters, as well as co-editor of two books on signature pedagogies and co-editor of Teaching & Learning Inquiry, the official journal of the International Society for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (ISSOTL). “SoTL Spotlight” is her ongoing feature on the CFT website. This is the first entry.

Harvard University has been making the news this month for its efforts to be “on the cutting edge of great change in teaching and learning,” according to the benefactor supporting the university’s new multi-million dollar Initiative for Teaching and Learning (Hauser qtd. in Walsh). The initiative is the campus’s response to increasing knowledge about how students learn (and don’t), a student body with changing needs, and “a growing concern at even the most elite institutions that the classroom experience is not all it could be” (Berrett). First came a daylong conference showcasing the innovations of Harvard faculty and bringing in big-name scholars who’ve done research on teaching and learning in their own fields. Next is a grant program to support evidence-based pedagogical innovations across campus.

Despite the headlines, this work is far from new. Even before 1990 when Ernest Boyer publicly expanded the notions of scholarship and research beyond the traditional “scholarship of discovery” to include a “scholarship of teaching” conducted by disciplinary experts in their own classrooms, many in higher education challenged the assumption that faculty highly trained in their disciplines can transmit that knowledge to students without intentionally understanding if, what, and how their students are learning.

Almost 15 years ago in “What’s the Problem?: The Scholarship of Teaching,” Randy Bass of Georgetown University (now the President of the International Society for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning [ISSOTL]) reflected on this assumption and the accompanying divide between the work we do as scholars and researchers, and what we do as teachers. He articulated a fundamental difference:

In scholarship and research, having a “problem” is at the heart of the investigative process; it is the compound of the generative questions around which all creative and productive activity revolves. But in one’s teaching, a “problem” is something you don’t want to have, and if you have one, you probably want to fix it. Asking a colleague about a problem in his or her research is an invitation; asking about a problem in one’s teaching would probably seem like an accusation. (Bass 1999)

The consequences of this difference include a culture of “habits and hunches” in how we think about our students’ learning (Berrett) and another culture of curiosity, inquiry, and systematic exploration, construction, and dissemination of knowledge within our disciplines. This internal culture war is what the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL), as it’s now called, aims to resolve by bringing the habits of mind, values, and practices we use in our disciplinary work into our classroom work.

I think of the thrill of potential discovery as I read a novel: moments that raise questions, that take me through the words on the page to explore the contexts in which they were written, that pull me to a dozen other novels and scholars in conversation with this passage, that stop me mid-page and slow my reading to a crawl. These moments of coming to my knees as I read are the “problems” that made me fall in love with literature—and more precisely, literary study. These moments make me want to jump up, rush to my peers, show them what I’ve found, and ask them what they see. In these moments, halted in my reading, feeling around in the nooks and crannies as I feel out the new layers of meaning, conversing with texts and peers, I am doing the work of a literary scholar. I’ll never forget when my groping around on all fours in graduate school helped me notice a pattern that ultimately became my dissertation. These are the moments of labor, investigation, discovery, and creation in my field.

through the words on the page to explore the contexts in which they were written, that pull me to a dozen other novels and scholars in conversation with this passage, that stop me mid-page and slow my reading to a crawl. These moments of coming to my knees as I read are the “problems” that made me fall in love with literature—and more precisely, literary study. These moments make me want to jump up, rush to my peers, show them what I’ve found, and ask them what they see. In these moments, halted in my reading, feeling around in the nooks and crannies as I feel out the new layers of meaning, conversing with texts and peers, I am doing the work of a literary scholar. I’ll never forget when my groping around on all fours in graduate school helped me notice a pattern that ultimately became my dissertation. These are the moments of labor, investigation, discovery, and creation in my field.

Imagine my disappointment when my literature students come across such a passage, and some cite it as a source of frustration and a reason to dislike literature classes, while others simply quit reading. At one point in my career, these responses might’ve been a bitter pill. This was not the conversation I wanted to have with my students. This was not what it meant to teach literature. My solutions might, at one time, have included immediately telling the students what those difficult passages meant, controlling discussion to prevent comments about their experience of reading, steering attention away from such passages, assigning less challenging texts, and other workarounds.

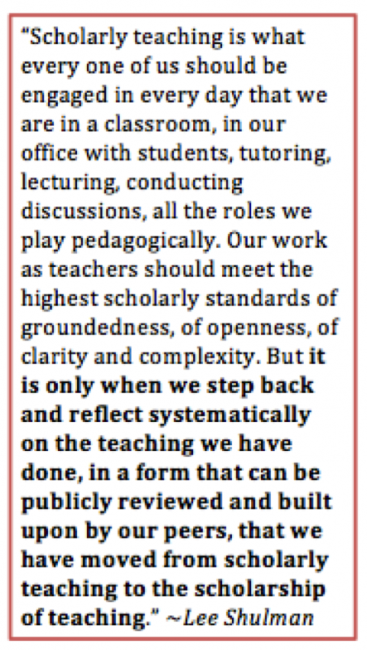

Early in my teaching days, however, I was invited into a future faculty program for graduate students and met the work of Randy Bass, who challenged me to think of my classroom “problems” differently; Ernest Boyer, who expanded what I’d learned about potential areas of research to include teaching; and Lee Shulman, who encouraged me to make my teaching “community property” by opening it up to investigation, conversation, peer review, and knowledge construction. With a couple of dozen other graduate students from across the university, we explored teaching and learning with the same sense of discipline and interest we brought to our home departments. I’ve thought about my students’ responses to literature very differently as a result, and I’ve done much to help my students and others’ approach texts in ways that more closely resemble the approaches of literary scholars.

Unlike my experience, most graduate student education perpetuates the distance between research and teaching—and how we view “problems” in each—by focusing solely on disciplinary training. I’ve now been at Vanderbilt for almost two months, and I see that things are a little different here. Graduate students can participate in a Teaching Certificate Program sponsored by the Graduate School and the Center for Teaching. They can also become Teaching Affiliates, and a few can become Graduate Teaching Fellows and Teaching-as-Research Fellows. These programs are designed to help future faculty observe, practice, study, and share teaching practices that are supported by research and evidence. Those completing the Teaching Certificate and the Teaching-as-Research Fellowship complete their own SoTL, or teaching-as-research, projects.

I’ve been listening to some of them describe their projects and what’s motivated them. In each conversation, I hear them framing teaching and learning “problems” in ways that reflect some of the curiosity and inquiry of disciplinary work:

- One teaches a popular gateway course in the sciences and observes that it often acts as a gatekeeper, preventing many students from continuing in the field and subsequently in a high-stakes profession. She’s developing a way to monitor student misunderstanding as it happens, rather than when they fail the exam and it’s too late.

- Another is interested in adult learners like her and how she can help them do well in class, rather than assuming that all students have the same needs. Based on her own experiences as a student older than most of her peers, she has had some good ideas but wants to test them.

- Another recalls a point of confusion she experienced as a student and worries that students newer to the field may share that confusion, so she wants to look closely at the traditional approach and identify the reasons for the confusion.

- Another loves his discipline and wants his students to recognize the elements that speak to him, rather than seeing the work as merely exercises in rote memory. He says his goal is not only to make his students appreciate the discipline but also to make them more complex thinkers.

- A team wants their non-majors to understand, appreciate, and persist in an upper-level course, so they’ve been experimenting with heterogeneous small-groups to measure whether peers who are majors engage non-majors more effectively than the non-peer groups of professors and teaching assistants.

- Another has identified a fundamental concept that serves as bottleneck for most students in his field and developed an activity that thus far seems to have effectively helped more students grasp the concept.

These conversations have been my introduction to SoTL at Vanderbilt. In my next few “SoTL Spotlights,” I’ll be sharing some of my conversations with Vanderbilt faculty engaged in this work–motivated not by a multi-million-dollar initiative but instead by their own curiosity. Stay tuned.

References

Bass, Randy. (Feb 1999). “The Scholarship of Teaching: What’s the Problem?” inventio: creative thinking about learning and teaching

Berrett, Dan. (Feb 5, 2012). “Harvard Conference Seeks to Jolt University Teaching.” The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Boyer, Ernest L. (1990). Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Jossey-Bass.

Shulman, L. S. (Nov. 1993). “Teaching as Community Property: Putting an End to Pedagogical Solitude.” Change. 6-7.

Walsh, Colleen. (Feb 6, 2012). “New Initiative for Better Teaching.” Harvard Gazette

Leave a Response