‘Educationally Purposeful’ Thoughts about Race on Campus

by Nancy Chick, CFT Assistant Director

This week, Vanderbilt is hosting the fourth annual Institute on High-Impact Practices and Student Success, sponsored by the American Association of Colleges & Universities (AAC&U). On the opening night, CFT Director Derek Bruff and I attended the plenary session, along with the 220 participants from as far away as the Marshall Islands and as close as Chattanooga. A common theme among the AAC&U’s plenary speakers was “equity-mindedness,” or “awareness of and proactive willingness to address [one’s] institution’s equity and inequity issues” (AAC&U Statement). We hear the word “equity” far less often than its cousins (e.g., “diversity,” “inclusion,” “tolerance”), but the plenary speakers and accompanying conversations reminded me of its significance.

Shaun Harper’s 2009 essay on equity (“Race-Conscious Student Engagement Practices and the Equitable Distribution of Enriching Educational Experiences”) has stuck with me as one of the clearest explanations of equity and “race-consciousness” in higher education. He shines a light on the complexities of “what has been routinely reported in higher education research concerning the disengagement and alienation of racial minorities at predominantly white institutions.” There is simply too much in the essay that’s quote-worthy, so I encourage you to read the whole piece, but for now, here are a few highlights.

Harper cautions us against overoptimism about high-impact practices (HIPs) of engagement: while it’s true that “college students who are actively engaged inside and outside the classroom are considerably more likely than their disengaged peers to persist through baccalaureate degree attainment,” it’s also true that “racial minority undergraduates are considerably less likely than their white peers to enjoy the educational benefits associated with them.” In other words, yes, the evidence shows that HIPs engage and help retain students, especially those who have historically had lower persistence rates in college; however, there is also overwhelming evidence that racial minority undergraduates are far less involved with these beneficial activities. In this way, the evidence of the effectiveness of HIPs is like the knowledge that we should eat more broccoli.

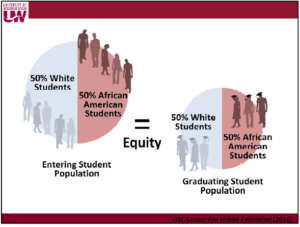

So, rather than continue using traditional models for engagement and assume “if we build it, they will come,” Harper looks closely at the language (and associated practices) for talking about race on campus, differentiating between “equality (treating all students the same) equity (giving students what they need to accrue the same outcomes as others in a particular context).” Harper’s nuance here has significant implications.

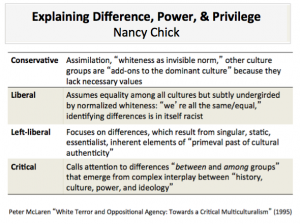

I’m reminded of a theoretical framework I draw on in all of my research (disciplinary, pedagogical, and faculty development). Peter McLaren’s (1995) multicultural theories, summarized in my old slide to the right, help us identify, understand, and analyze how we talk about difference–any kind of difference. Parallel to focusing on “equality” by “treating all students the same” is McLaren’s notion of “liberal multiculturalism” in their erasing of differences and assumption that the what works for some (often those in power) what works for everyone, regardless of experience or need. “Equity,” then, mirrors McLaren’s “critical multiculturalism” in recognizing what Harper calls “qualitative differences in the experiences of racial minority students.” I appreciate this theoretical framework for giving us a broader way of making sense of the complexities around us, especially those moments when we encounter anything we recognize as “different.”

To ground this theory in something more concrete, look at how Harper handles the buzzword of “engagement”:

In my view, effective educators treat engagement as a verb, rather than a noun, and attribute the presence of engagement inequities to institutional dysfunction. That is, the popular approach of only determining what students do to become engaged must be counterbalanced by examinations of what educators do to engage students. Put differently, questions concerning effort must be shifted from the individual student to her or his institution. Effective educators avoid asking, what’s wrong with these students, why aren’t they getting engaged? Instead, they aggressively explore the institution’s shortcomings and ponder how faculty members and administrators could alter their practices to distribute the benefits of engagement more equitably. Accepting institutional responsibility for minority student engagement and success is the first step to race-conscious educational practice.

Harper asks us to consider this notion of “race-consciousness,” rather than “colorblindness,” which is “an overused and offensive way of denying the unique experiential realities of racial minority students in predominantly white situations.” Instead, being aware of these experiential realities compels us to ask “what is possible when educators and administrators take seriously the responsibility of engaging diverse student populations in educationally purposeful ways.”

Educationally purposeful ways. I love that phrase. It’s what the folks attending the HIPs Institute are talking about this week in our Student Life Center. It’s also at the heart of our mission at the CFT. I look forward to thinking more about these issues and extending the conversations across campus.

References

Harper, Shaun R. “Race-Conscious Student Engagement Practices and the Equitable Distribution of Enriching Educational Experiences.” Liberal Education, 95.4 (2009.)

McLaren, Peter. “White Terror and Oppositional Agency: Towards a Critical Multiculturalism.” Multicultural Education, Critical Pedagogy, and the Politics of Difference. NY: SUNY Press, 1995. 33-70.

Leave a Response