Writing as a Design Process

by Derek Bruff, CFT Director

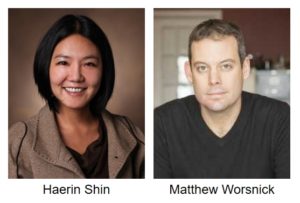

On Tuesday, November 6th, the CFT’s learning community on teaching design thinking hosted a lively conversation about writing as a design process. Both writing and design involve knowing one’s audience and being intentional about feedback and revision. We invited Haerin Shin, assistant professor of English, and Matthew Worsnick, assistant professor of the practice of history of art, to speak with the group about the parallels they see between writing and design.

Worsnick opened the conversation with a story about a time he realized the power of design thinking. After a few years teaching high school English, Worsnick started architecture school. While working on a semester-long design project in a studio class, he took the same approach he took with his 10th grade writing students: He identified a thesis, in this case it focused on blending old and new buildings in a city block, and just kept revising his work based on that thesis. He felt comfortable with this logical, systematic approach, but for the architecture project, it just didn’t “sing,” as Worsnick said.

Worsnick opened the conversation with a story about a time he realized the power of design thinking. After a few years teaching high school English, Worsnick started architecture school. While working on a semester-long design project in a studio class, he took the same approach he took with his 10th grade writing students: He identified a thesis, in this case it focused on blending old and new buildings in a city block, and just kept revising his work based on that thesis. He felt comfortable with this logical, systematic approach, but for the architecture project, it just didn’t “sing,” as Worsnick said.

Worsnick noticed that one of his fellow students in the design studio took a very different approach. This student started his project focused on pedestrian flow, but when he invited feedback on his draft from the class, one comment about the relationship between commercial and residential buildings captured his attention. He redesigned his entire city block around that relationship, then shared the new plans. Again, one comment, this time about the ways the built environment shapes socioeconomic hierarchy, inspired him to go back to the drawing board. His final project didn’t solve his initial problem of pedestrian flow, but it was, as Worsnick said, a really great inspiring design.

This experience showed Worsnick what can be created when one is open to feedback and dramatic revision. He now brings this generative approach to his design work – as an art historian, this includes consulting with museums on exhibit design – and to his writing instruction. As a writing assignment, he will ask students to take an obscure sentence in one essay and turn it into a thesis for a subsequent essay. He tells his students to start writing not with an answer, but with a question. Like a designer, you may not know what the answer is when you start the process, but with messy drafts and peer feedback and an openness to dramatic revision, you can end up with a piece of writing that sings.

Shin also spoke to the key role of revision in the writing and design processes. Before graduate school, she spent six years in the software business, most of that time translating from Korean to US English. She noted that the grammar of the two languages are very different, which means good translation involves a lot of “taking things apart and putting them back together.” Shin sees that as an essential element of writing, noting that the kind of critical writing one does in an English major can also be creative writing. Shin likes to give students assignments that combine critical and creative writing. For example, she will ask students to rewrite the ending of a Raymond Chandler piece that has an “odd” ending. This requires students to think about plot, but also voice and diction as they try to adopt Chandler’s style. Shin said that this was “way better than sitting around talking about voice and diction.”

Through these kinds of creative assignments, Shin directs her students to think about the process of writing. Another assignment she mentioned involved asking her students try their hand at collaborative writing. She will have students write responses to the text at hand in small groups using Google Docs. This gives students a chance to see other students’ writing processes in action, and Shin prompts her students to reflect on the differences they see. They often see how non-linear writing can be. This is disconcerting for some students, who might like a more receipt-like approach to writing, but Shin says that fragmented writing is already part of her students’ daily like, like the texting they do while walking across campus. She helps her students find meaning and arguments through divergent thinking… just like designers do as they brainstorm and prototype.

During the discussion, I asked how instructors in the room help students get comfortable making significant revisions to their work. I’ve found that many students see revision as something that happens at a very granular level – a new sentence here, a revised phrase there. Substantial revision, like what Worsnick described, isn’t always something students want to take on. Worsnick said that he’ll ask students to write a 2000-word draft for a 500-word essay. “Just start writing about what you see in the artifact in front of you,” he’ll tell students. “Just keep writing.” Then edit it into something interesting.

One instructor in the room noted that the kind of creative assignments Shin mentioned often motivate students to put the time in for revision, moreso than traditional assignments. And another said that she uses Turnitin, the plagiarism checker, to have students compare revisions. She’ll ask students to write new drafts that are no more than 40% similar to their first drafts. “The design process isn’t linear, it’s iterative,” Shin said. “When students understand this, they can be more okay with false starts and failure and revision.”

We also discussed the parallels between audience in the writing process and users in the design process. One faculty member mentioned that she’s not crazy about the metaphor of “users” or “clients” when talking about writing, but she sees empathy as an important part of both writing and design. How can you get out of your own headspace and see how one’s work might be received by another? Shin said that the “user” framing can be useful when one considers things like titles and abstracts. How might others research a topic, and how can you craft your work can be found by those who will find it valuable?

While noting the value of authentic audiences outside a classroom, Worsnick said that he has reconciled himself with the necessity of an imagined audience. He might frame a writing assignments for his students as a New Yorker “Talk of the Town” piece or, for more experience students, a book review. I noted that students often write for an audience of one: their instructor. That’s artificial, and it’s not particularly motivating. Connecting our students to authentic audiences, even imagined ones, helps them get out of their headspace and, as one instructor present said, “understand how one’s writing is creating a story for someone else.”

Thanks to Matthew Worsnick and Haerin Shin for leading a lively discussion about writing and design! For information on upcoming conversations on teaching design thinking, just ask me (derek.bruff@vanderbilt.edu) to add you to our mailing list.

Leave a Response