What’s In Your Syllabus?

by Nancy Chick, CFT Assistant Director

I just posted my syllabus on YES (Your Enrollment Services, where students register online) as part of Vanderbilt’s effort to help students make informed choices about their courses, and I had a moment of anxiety. Like Anne Bradstreet in “The Author to Her Book,” despite my worries that it’s “unfit for light,” it’s now “exposed to public view.” How will prospective students read and understand my syllabus? What does it tell them about my teaching? What do I think it tells them about my teaching?

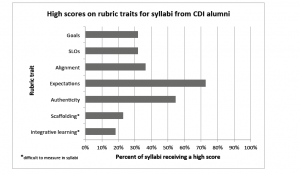

A recent study points to the challenge of relying on a syllabus to make judgments about a course or an instructor. In “The Impact of the Course Development Institute on Faculty Practice,” Metzler, Rehrey, and Kurz (2013) analyzed syllabi, major assignments, and their rubrics to measure the impact of a summer course design workshop on participants’ actual classes. They also surveyed the participants about their intentions and perceptions of this impact. The researchers used this rubric to analyze the syllabi as direct evidence of participants’ teaching, specifically looking for seven factors that align with the workshop’s curriculum: course goals, student learning outcomes, alignment of assessment and activities with course goals, expectations of student performance, authenticity of assessments, scaffolding of learning activities, and integrative learning.

Their analysis of syllabi suggests “more modest transformations of their classroom teaching” than the amount of change reported in the surveys; however, the researchers concluded that they’d in fact measured “thinking, feeling, and beliefs about teaching,” rather than “changes in classroom teaching practice.” Although the findings were useful in some ways, Metzler, Rehrey, and Kurtz acknowledge that the course documents didn’t show what actually happens in the classroom.

When I first heard about this study, I saw it–like Vanderbilt’s efforts to give students more information about our classes–as a challenge to make sure my syllabus documents more than the course’s policies, topics, and schedule.* Like poems, our syllabi are ultimately read by broader audiences than we initially write for, and we can’t control how they are interpreted. Like it or not, readers will use these texts to make significant inferences about our level of rigor, our personalities, and even our intentions.

—

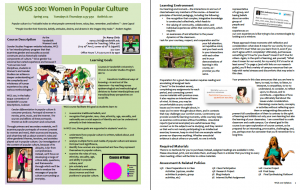

* To the right is the syllabus I just posted to YES and the course website. Again, like Bradstreet, no matter how much “I washed thy face,… the more defects I saw, / And rubbing off a spot, still made a flaw.” I tried to make both the content and the form more illustrative of this specific course (WGS 200: Women in Popular Culture) and how I teach it. My revised literature syllabi will look quite a bit different.

For more information on constructing your syllabus (the basics to extra considerations like the above), see the CFT’s guide on Syllabus Construction.

Reference

Metzler, Eric, Rehrey, George, & Kurz, Lisa. (8 Nov. 2013). The Impact of the course development institute on faculty practice. Presentation at the Conference of the Professional and Organizational Development (POD) Network, Pittsburgh, PA. 59.

Leave a Response